Early Russian History: The Kievan Rus’ to the Collapse of the Russian Empire

Russia is a vast country that has had a significant impact on the world’s cultural, political, and economic landscape for centuries. Its history spans over a thousand years, from the early days of the Kievan Rus’ to the present day. To understand the complexities of modern-day Russia, it is crucial to examine early Russian history, which is marked by various themes such as territorial expansion, the concentration of power, and revolution and reform.

This article aims to provide an introduction to the early history of Russia, tracing its evolution from a loose confederation of tribes to the emergence of one of the world’s most powerful empires and the eventual collapse of the Tsarist regime. Understanding Russia’s early history provides a foundation for comprehending its subsequent political, economic, and social development. This article will provide an overview of the key events and developments in early Russian history, from the formation of the Kievan Rus’ to the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917.

Want to discover the historical sites Russia has to offer? Be sure to check out my Russia Travel Guide to help you plan your trip!

Last updated: 4/16/23

Contents

- The Kievan Rus’ (882–1240)

- The Mongols (1240-1481)

- The Muscovite Period (1263–1547)

- The House of Romanov (1613-1917)

- The Russian Empire (1721-1917) & Peter the Great (1682–1725)

- Peter II (1727-1730)- Catherine the Great (1762-1796)

- The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815)

- The Decembrist Revolt (1825)

- Tsar Nicholas I (1825-1855)

- The Crimean War (1853-1856)

- Tsar Alexander II (1855–1881) & the Abolition of Serfdom (1861)

- Tsar Alexander III (1881–1894)

- Tsar Nicholas II (1894-1917)

- More on Early Russian history

Early Russian History: The Kievan Rus’ to the Collapse of the Russian Empire

The Kievan Rus’ (882–1240)

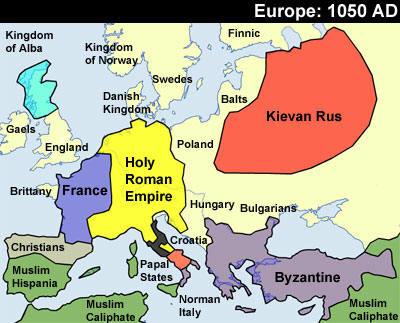

The history of Russia is believed to begin in the 9th century when a group of Slavic tribes in Eastern Europe formed a loose confederation called the Kievan Rus’. The exact date of the formation of the Kievan Rus’ is debated among historians, but the most commonly accepted year is 882 when the legendary Viking leader Oleg of Novgorod established the city of Kiev as his capital. This event marked the beginning of the process of unifying the disparate Slavic tribes under a single ruling authority, which laid the foundation for the emergence of the Russian state.

The society of the Kievan Rus’ was structured around a hierarchy of nobles, or boyars, who held power and wealth, and the common people who worked the land. At the top of the hierarchy was the Grand Prince, who ruled over the federation of tribes and held the highest level of power and authority. The Grand Prince was supported by a council of boyars, who were members of the noble class and held significant influence in the government. Below the boyars were the lesser nobility, or dvoryane, who served as local officials and military commanders. The majority of the population of the Kievan Rus’ were peasants, who worked the land and paid tribute to their local rulers. Some of these peasants were serfs, who were tied to the land and could not leave without their lord’s permission. In addition to the peasants, there were also merchants, craftsmen, and other urban dwellers who lived in cities such as Kiev and Novgorod.

After Vladimir the Great, the ruler of Kievan Rus’, introduced Orthodox Christianity in the 10th century, religion played a significant role in Kievan Rus’ society. The Church was closely tied to the ruling class and provided a unifying force for the diverse population of the Kievan Rus’. Education and literacy were also important in Kievan Rus’ society, with schools and libraries established in major cities and the Cyrillic alphabet developed to write Old Church Slavonic, the liturgical language of the Orthodox Church.

The fall of the Kievan Rus’ was a complex process that occurred over several centuries and involved various factors. One significant factor was internal division and conflict among the ruling elite, which weakened the federation and made it vulnerable to external threats. The fragmentation of the Kievan Rus’ into competing principalities, each with its own ruler, eroded the central power of the Grand Prince and made it difficult to maintain a cohesive state. The infighting would lead to their ultimate demise, and in 1237-1240, the Mongols invaded and conquered much of the territory of the Kievan Rus’.

The Mongols (1240-1481)

The Mongols, who established the Golden Horde, ruled over the Russian principalities for over two centuries, from the 13th to the 15th century. During this time, the Mongols exacted tribute from the Russian principalities, which drained the Russian economy. Additionally, the Mongol invasion destroyed the city culture of the Kievan Rus’ and led to the rise of new centers of power in Moscow, Tver, and Nizhny Novgorod. Locally, however, the Mongol domination allowed the Russian principalities to maintain a degree of autonomy in their internal affairs. The princes were allowed to rule largely as they saw fit, and the Russian Orthodox Church even experienced a spiritual revival under the leadership of Metropolitan Alexis and Sergius of Radonezh. Moreover, under Mongol rule, the Russian principalities developed a system of taxation, a postal road network, and military organization. The chronic insecurity in Russian political culture due to the geographic exposure that allowed the Mongol domination would leave a mark on Russia, however, that can still be seen to this day.

The Muscovite Period (1263–1547)

In 1480 Ivan III (also known as Ivan “The Great”) (1462-1505) led an army that defeated the Khazan and Astrakhan khanates, effectively ending the Mongol occupation and stimulating Russian expansion. Throughout his rule, Ivan the Great extended his influence over the territories of northeastern Rus’, signifying the start of Muscovite supremacy over the lands of Rus’.

The geography of Russia, however, presented many challenges, with no natural stopping points in any direction. The territory of the Russian state began to expand outward in search of more fertile land, and eventually, more than 120 nationalities would call Russia their home, but with no particular group having a claim to all of it. The Tsar was seen as the leader of “all the Russians,” but the open frontier made it difficult to secure the loyalty of peasants and nobles. This led to insecurity for landowners, who could not count on their workers to stay on their land and work the fields. Grand Prince of Moscow Ivan “The Great” sought to address this issue by implementing conditional service, allowing the Tsar to take back land from the boyars, a noble class, who owned it outright. This tied peasants to the land they farmed, resulting in the establishment of serfdom, which would last until its abolition in 1861. He also initiated a campaign of building and expanding the Moscow Kremlin, which became the symbol of Russian state power. The fall of the Mongols and the consolidation of power by Ivan III marked the beginning of a new era in Russian history, known as the Muscovite period.

Ivan the Great was succeeded by his son, Vasily III, who ruled as the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1505 to 1533. Vasily III continued the consolidation and expansion of Moscow’s power through the incorporation of several other territories into the Grand Duchy of Moscow. He also oversaw the construction of important buildings in Moscow, such as St. Basil’s Cathedral. Following Vasily III’s death, his son, Ivan IV, also known as Ivan the Terrible came to power in 1533. At the time, however, Ivan IV was only three years old, so his mother served as regent until his coronation in 1547. Ivan IV went on to become the first Tsar of Russia in 1547, and he ruled until his death in 1584. Ivan IV is known for his significant military conquests, his centralization of power, and his often brutal treatment of his subjects, earning him the moniker “the Terrible”.

Unfortunately, Ivan IV’s love life was less than perfect. Historical records suggest that Ivan IV had as many as eight wives, although only four were officially recognized by the Church. Three of his wives were even rumored to have been poisoned, purportedly by his political enemies or rivaling aristocratic families who aimed to marry their daughters to Ivan. Despite his romantic obstacles, Ivan the Terrible fathered nine children during his reign, including his successor Fyodor I Ivanovich.

Having to grow up in the dark shadow of his father, Feodor I lacked interest in politics and allowed his wife Irina’s brother, Boris Godunov, to serve as the de facto ruler of Russia. Most crucially, however, was the consequence of Feodor I’s death in 1598 without any heirs. This marked the end of the Rurik dynasty and triggered a period of instability in Russian history known as the Time of Troubles. The Time of Troubles was a period of succession crises during the Polish-Muscovite War of 1605-1618, where several pretenders and imposters (False Dmitris) vied for the throne. This time period was marked by famine, social unrest, and foreign intervention, and Russian nobility found itself searching for a new dynasty.

The House of Romanov (1613-1917)

They found their new monarch in Mikhail Romanov, a young nobleman who was elected tsar in 1613, thereby beginning the House of Romanov. Mikhail Romanov was chosen as a compromise candidate due to his noble lineage, youth, and lack of political ambitions. He was also seen as a unifying figure who could bring stability and restore order to the country.

The early Romanov rulers were not strong, with Mikhail sharing the throne with his father, Patriarch Philaret, during the crucial years of his reign. During Mikhail Romanov’s rule, however, Russia expanded its territory to include most of Siberia from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.

Alexei Mikhailovich, Mikhail’s son, came to power at the age of 16 in 1645 and was heavily influenced by Boris Ivanovich Morozov and then Patriarch Nikon. After the death of Alexei Mikhailovich, his son Fedor III briefly became Tsar in 1676 but died after only six years on the throne. During this period, government power often rested in the hands of individuals who had personal influence over the tsars.

The period from 1682 to 1725 was marked by the turbulent regency of Sophia Alekseyevna (until 1689), the joint rule of Ivan V and Peter I (also known as “Peter the Great”), and the following thirty years of Peter’s effective leadership.

The Russian Empire (1721-1917) & Peter the Great (1682–1725)

Starting in 1721, the Russian Empire emerged as the final period of the Russian monarchy. The Empire succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad and spanned most of northern Eurasia. During this time, Russia became a significant player in European “great power politics,” largely thanks to Tsar Peter I (1689-1725). Peter I, or “Peter the Great”, modernized and westernized Russia, transforming it from a medieval state into a European power. He established the city of St. Petersburg as the new capital, – or, rather, commanded thousands of surfs to build it for him – introduced new technologies and reforms, and made Russia a major player in international affairs.

Peter the Great recognized the need for modernization and reform in Russia. He believed that Russia’s future success depended on its ability to compete with the European powers, which meant adopting their modern technologies, science, and political institutions. To that end, he introduced a series of sweeping reforms that transformed the country in almost every aspect. Regarding the military, Peter introduced a new system of conscription, which required every nobleman to provide a certain number of soldiers for the army. He also reorganized the army and navy, bringing them in line with European standards. Peter also created a modern bureaucratic state, with government officials appointed on merit rather than birth. During his reign, a new system of taxation was created and a central treasury was established. Capitalizing on his new capital’s strategic location, he encouraged foreign trade and established new ports, canals, and roads to facilitate commerce.

Peter II (1727-1730) – Catherine the Great (1762-1796)

Peter the Great was succeeded by his wife’s nephew, who became Emperor Peter II. Peter II ruled Russia from 1727 until his untimely death at the age of 14 in 1730. During his short reign, Peter II continued some of the policies of his predecessor, but he was mostly influenced by his tutors and advisers. His sudden death led to a succession crisis, and Anna Ivanovna, the daughter of Peter the Great’s half-brother Ivan V, was chosen by the Supreme Privy Council to become the next ruler of Russia.

After Anna Ivanovna, several rulers took the throne of Russia. She was succeeded by her infant grandnephew Ivan VI, who was only a few months old at the time. Ivan VI’s mother, Anna Leopoldovna, acted as regent, but her rule was challenged by Elizabeth, the daughter of Peter the Great and Catherine I, who was backed by the powerful guards regiments. In a coup in 1741, Elizabeth took the throne and ruled until her death in 1762. She was succeeded by Peter III, who was overthrown by his wife Catherine the Great in a palace coup shortly after his ascension to the throne. Catherine ruled Russia from 1762 until 1796 and is known for her introduction of the Golden Age in Russia, expansion of the Russian Empire, administrative and legal reforms, and patronage of the arts and sciences.

Catherine made significant investments in Russia’s military, by expanding the navy and improving the training of soldiers. She also oversaw a number of successful military campaigns, including the annexation of Crimea and the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. During her reign, she created a new legal code, the “Charter to the Gentry,” which was based on the principles of Enlightenment thought. While the code granted more rights to the middle class and peasantry, and abolished torture and capital punishment, its impact on the lives of ordinary Russians was limited. Administratively, Catherine reorganized the structure of Russia, dividing it into provinces and districts, each with its own governor. She also established a Council of State to advise her on government matters.

Catherine also had an immense impact on education in Russia during her reign. She established a network of schools, universities, and encouraged the education of girls and women. In 1764, she founded the Smolny Institute for Noble Maidens in St. Petersburg, which was the first state-funded educational institution for girls in Russia. She also supported the growth of literature, music, and theater in Russia. One of her most recognizable contributions today is the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg’s Palace Square. Today, the Hermitage houses one of the largest art collections in the world with over 3 million works of art. Overall, Catherine’s reforms aimed to bring Russia more in line with the principles of the Enlightenment and improve the lives of its citizens. Although her reforms were not always successful, they were a significant step towards modernizing Russia and establishing it as a major European power.

After Catherine the Great’s death in 1796, her son Pavel I became the ruler of Russia. Pavel I had a strained relationship with his mother and sought to reverse many of her policies and reforms. He also pursued a more conservative foreign policy and aligned Russia with Prussia rather than with Austria, which had been Catherine’s preferred ally. These policies made him quite unpopular among both his advisors and nobles, and after a few years a conspiracy was underway. Pavel I of Russia was assassinated in 1801 by members of the Russian aristocracy and military, and his son, Grand Duke Alexander, ascended to the throne. Unlike his father, Alexander I continued many of Catherine’s policies and pursued an ambitious program of reform and modernization. Alexander I’s reign was characterized by a series of major conflicts, including the Napoleonic Wars, which had a significant impact on Russia and Europe as a whole.

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815)

The French invasion of Russia in 1812 was a catastrophic military campaign undertaken by Napoleon Bonaparte, the Emperor of France, against the Russian Empire under the rule of Tsar Alexander I. The invasion was a part of the Napoleonic Wars, which were fought between France and a coalition of European powers, including Russia, Britain, and Prussia. As the French army advanced deeper into Russia, it encountered fierce resistance from Russian troops, who employed guerilla tactics and harassed the invaders. Despite initial victories, the French army was plagued by supply shortages, disease, and desertion. By the time the Grand Armée reached Moscow in September 1812, it had lost over 200,000 men.

The capture of Moscow did not bring about the decisive victory Napoleon had hoped for. The city was abandoned by the Russians, and fires set by retreating Russian troops destroyed much of the city, leaving the French army with few supplies or shelter. Napoleon’s army remained in Moscow for several weeks, hoping to negotiate a peace settlement with Alexander I. However, the Russians refused to negotiate, and the French army was forced to retreat. The retreat was disastrous, as the French army faced harsh winter conditions and attacks by Russian forces. By the time the remnants of the Grand Armée crossed the Niemen River in December 1812, it had lost over 400,000 men, including many of its best soldiers and officers. The Russian campaign was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars, marking the beginning of Napoleon’s decline and the start of Russia’s rise as a European power.

The Decembrist Revolt (1825)

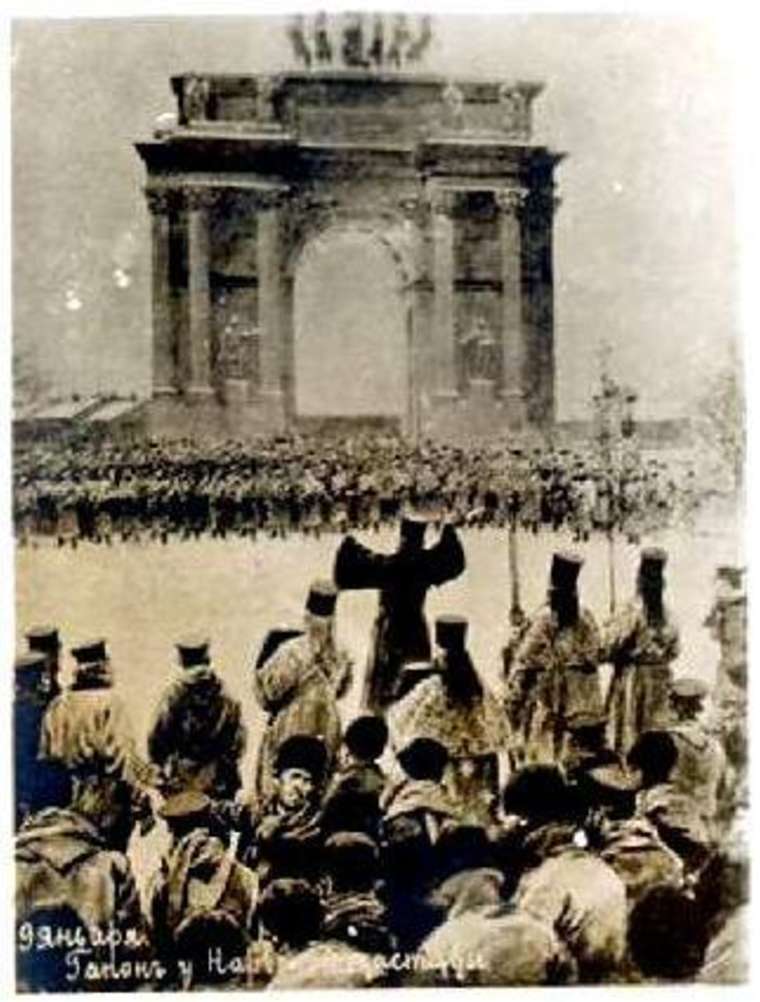

A critical moment in Russian history came after Alexander I’s untimely death known as the Decembrist revolt. The Decembrist revolt was a political uprising that took place in Russia on December 14, 1825. The revolt was led by a group of upper-class military officers and liberal intellectuals who were dissatisfied with the autocratic regime of Tsar Alexander I and were calling for political reform.

The Decembrists, as they came to be known, were inspired by the liberal ideas that were spreading throughout Europe at the time, and they sought to establish a constitutional monarchy in Russia. They were also influenced by the ideals of the French Revolution, as many of them had participated in military campaigns in France or other parts of western Europe. During a period of political upheaval following the death of Tsar Alexander I, one secret Dekabrist group known as the Northern Society incited an uprising by convincing some St. Petersburg troops to refuse loyalty to Nicholas I and instead demand the accession of his brother Constantine. However, the rebellion was disorganized and easily crushed, with Colonel Prince Sergey Trubetskoy fleeing immediately. Another insurrection in the south by the Chernigov regiment was also quickly defeated. After an investigation led by Nicholas I himself, 289 Decembrists were put on trial, with 31 imprisoned, 253 banished to Siberia, and 5 executed.

Despite its failure, the Decembrist revolt marked a significant turning point in Russian history. It was the first organized attempt to overthrow the autocratic regime and to establish a more democratic system of government in Russia. The ideals and principles of the Decembrists continued to inspire later generations of Russian liberals and revolutionaries, and they played a significant role in the development of Russia’s political culture in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Tsar Nicholas I (1825-1855)

During his reign, Nicholas I introduced a series of reforms aimed at modernizing Russia and strengthening the autocratic government. In the aftermath of the Decembrist Revolt, he created a secret police force, known as the Third Section, to monitor and suppress dissent. He also introduced strict censorship laws to control the press and limit free expression.

Nicholas I was also known for his conservative social policies. He opposed the liberalizing trends that were sweeping across Europe at the time, and he sought to maintain the traditional values and institutions of Russian society. He banned the publication of books that he deemed immoral or subversive and tightened restrictions on universities and educational institutions.

In terms of foreign policy, Nicholas I pursued an expansionist agenda, seeking to extend Russian influence in Europe and Asia. Through the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829 and the Russo-Persian War of 1826-1828, Russia gained substantial territory in the Caucasus. Although he did not live to see it through, his final conflict he led Russia into, the Crimean War, would not end as successfully as his previous conquests.

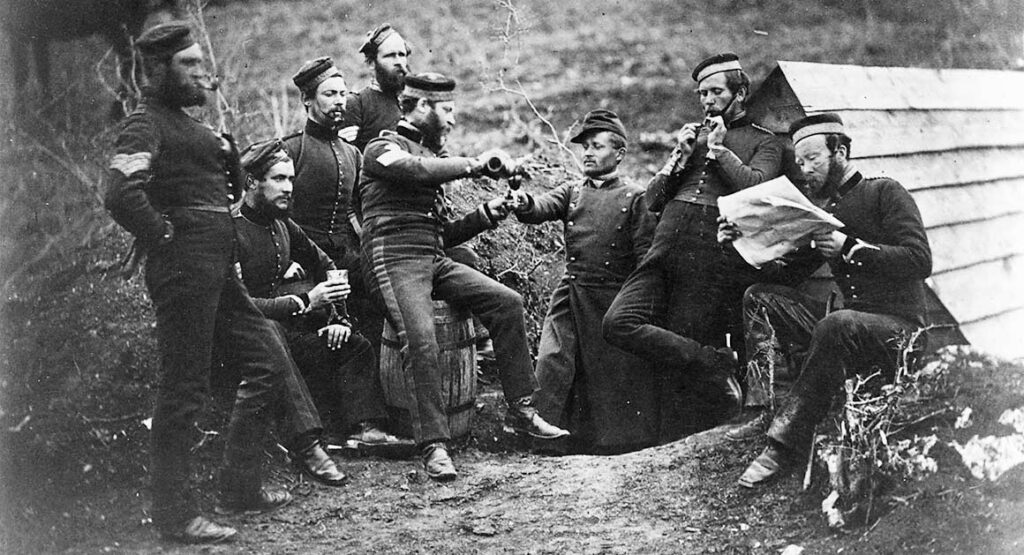

The Crimean War (1853-1856)

The Crimean War was a major military conflict fought between Russia on one side and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain, and Sardinia on the other. The war lasted from 1853 to 1856 and was primarily fought on the Crimean Peninsula, a region in the Black Sea. The immediate cause of the war was Russia’s attempt to expand its influence in the Balkans, which threatened the balance of power in Europe. France, Britain, and the Ottoman Empire, who were opposed to Russian expansion, formed an alliance to prevent it.

The war saw significant military action, including major battles at Alma, Balaclava, and Inkerman. The most famous engagement of the war was the Siege of Sevastopol, a protracted and bloody struggle that lasted for over a year and saw significant losses on both sides. The war had a significant impact on the region and on European politics as a whole. It highlighted the declining power of the Ottoman Empire and the rising influence of other European powers. It also saw significant technological and strategic developments, such as the use of railways, telegraphs, and modern rifles.

The Treaty of Paris, which ended the war, saw Russia lose control of several territories, including parts of Bessarabia and the Caucasus, and it also limited the Russian navy’s presence in the Black Sea. The war had a devastating impact on Russian society, contributing to growing discontent and sparking reforms under Tsar Alexander II.

Tsar Alexander II (1855–1881) & the Abolition of Serfdom (1861)

Tsar Alexander II came to power following the death of his father, Nicholas I, in 1855. The Russian loss in the Crimean War had a significant impact on Alexander II’s reign. The war exposed the weaknesses of the Russian Empire, including its outdated military tactics, poor infrastructure, and lack of technological advancements. The humiliating defeat also led to a sense of national crisis and contributed to growing calls for reform within Russia.

In the aftermath of the war, Alexander II realized that Russia needed significant modernization and reform in order to compete with the other European powers. He recognized that the old system of serfdom was unsustainable and abolished it in 1861. This reform was a major milestone in Russian history and was followed by other reforms, such as the establishment of local self-government and the creation of an independent judiciary.

However, Alexander II’s reforms were not enough to satisfy everyone. The reforms created new social and economic tensions, and many people, including the revolutionary movement, felt that they did not go far enough. This dissatisfaction culminated in his assassination by members of the revolutionary group “People’s Will” in 1881. The assassination also sparked a period of political and social upheaval in Russia, which ultimately led to the Russian Revolution in 1917.

Tsar Alexander III (1881–1894)

In the direct aftermath, the assassination of Tsar Alexander II marked the beginning of a new era of political repression and state-sponsored terrorism in Russia. Alexander II’s son, Alexander III, rose to power and heavily employed political repression and the suppression of dissent.

Alexander III was a reactionary ruler who opposed the liberal reforms that his father had introduced. He believed in the absolute power of the Tsar and worked to strengthen the autocratic system of government that had been in place in Russia for centuries. He worked to centralize power and to limit the authority of regional and local governments. He also pursued a policy of Russification, which aimed to promote Russian culture and language at the expense of other nationalities within the Russian Empire.

Despite his conservative policies, Alexander III also oversaw a period of economic growth and industrialization in Russia. He invested heavily in infrastructure, including the expansion of the railway network, and encouraged foreign investment in Russian industries. Alexander III’s reign came to an end in 1894, when he died of kidney disease at the age of 49. He was succeeded by his son, Nicholas II, who would go on to become the last Tsar of Russia before the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Tsar Nicholas II (1894-1917)

Nicholas II was the last Tsar of Russia, ruling from 1894 to 1917. His reign was marked by significant political, social, and economic turmoil, which ultimately led to the collapse of the Russian Empire and the rise of the Soviet Union. During Nicholas II’s rule, Russia underwent significant industrialization and modernization. The country saw rapid economic growth and the emergence of a new middle class. However, this growth was accompanied by rising social and economic tensions, including widespread poverty and inequality.

Nicholas II also faced significant political challenges during his reign. He ruled as an autocrat and resisted calls for political reform, leading to growing discontent among the Russian people. The country was rocked by a series of protests and uprisings, including the Bloody Sunday massacre in 1905, which led to widespread demands for political change.

In response to these pressures, Nicholas II agreed to the creation of the Duma, a parliamentary body that was meant to give the Russian people a voice in government.

However, the Duma was weak and ultimately failed to address the underlying problems of the Russian Empire. During World War I, Nicholas II took direct control of the military, hoping to boost morale and win the war. Unfortunately, the war effort proved disastrous for Russia, leading to significant military losses and economic hardship. The country was wracked by food shortages and other forms of deprivation, and there were growing calls for an end to the war.

Nicholas II’s rule came to an end in 1917, when he was forced to abdicate following the February Revolution. The Provisional Government that took power after his abdication was unable to address the underlying problems of the Russian Empire, leading to the October Revolution and the rise of the Soviet Union.

More on Early Russian history

Learning about early Russian history is crucial to understanding Russia today because it provides valuable insights into the country’s culture, traditions, and political system. Many of the customs and beliefs that are still prevalent in Russian society today can be traced back to this period. For example, the strong centralization of power in the Russian state can be traced back to the rule of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century. Similarly, the influence of the Eastern Orthodox Church on Russian culture and politics can be traced back to the Christianization of the Kievan Rus’ in the 10th century.

Additionally, understanding the challenges and successes of early Russian history can shed light on current issues facing the country. For instance, the Russian Revolution of 1917 and subsequent establishment of the Soviet Union can be better understood by examining the economic and social conditions of pre-revolutionary Russia. In short, a deep knowledge of early Russian history is essential for anyone seeking to gain a comprehensive understanding of Russia today, its people, its government, and its place in the world. I hope this article served you well, and taught you something new! Do you have any interesting facts to add? Write them in the comments below!

Works Cited

“Biography of Peter the Great of Russia.” Saint-Petersburg.com, 2023, www.saint-petersburg.com/royal-family/peter-the-great/.

Hunter, Allyson. “Cultural Changes of Russia under the Mongols | History, Impact & Influences – Video & Lesson Transcript | Study.com.” Study.com, 2022, study.com/learn/lesson/cultural-changes-russia-mongols-history-impact-influences.html.

“Kievan Rus | Historical State, Europe | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2023, www.britannica.com/topic/Kyivan-Rus.

Marlatt, Ethan. “The Decembrist Revolt of 1825 | COVE.” Covecollective.org, 11 Oct. 2020, editions.covecollective.org/content/decembrist-revolt-1825.

“Michael Romanov (Russia) (1596–1645; Ruled 1613–1645) | Encyclopedia.com.” Encyclopedia.com, 2013, www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/michael-romanov-russia-1596-1645-ruled-1613-1645.

“Romanov Family: Facts, Death & Rasputin – HISTORY.” History.com, 30 Aug. 2022, www.history.com/topics/european-history/romanov-family.

“Russian Empire | History, Facts, Flag, Expansion, & Map | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2023, www.britannica.com/place/Russian-Empire.

“Russian Empire: Overview, History & Expansion | StudySmarter.” StudySmarter UK, 2023, www.studysmarter.co.uk/explanations/history/modern-world-history/russian-empire/.

“Timeline of the Crimean War – Historic UK.” Historic UK, 2019, www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Timeline-Crimean-War/.

Wyse, Liz. “The Rise and Fall of Kievan Rus – the Map Archive.” The Map Archive, 28 Feb. 2022, www.themaparchive.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-kievan-rus/.

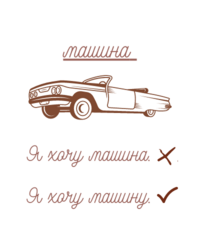

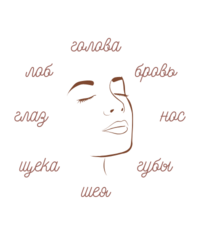

Learn to speak russian

Travel with ease & dive into the culture, history & lifestyle of post-Soviet countries

free russian learning materials

Melissa

Get the Goods

Head over to the Language & Travel Shop to check out my favorite goodies I use for learning Russian and traveling! I've compiled all my favorite products I use when #onthebloc so that you can benefit from them when you travel abroad. Help yourself prepare and support this blog at the same time :) Счастливого пути!

carry-on goods

gifts for travelers

photography

apparel & accessories

textbooks & readers

luggage & bags

categories

#oTB essentials

Russian-Speaking Travel Destinations

use your new russian skills in real life!

Belarus

EASTERN EUROPE

central Asia

central Asia

Eurasia

Russia

Kyrgyzstan

armenia

Moldova

Kazakhstan

eastern europe

read »

read »

read »

read »

read »

read »

The caucasus

travel guides

Get your FREE #OnTheBloc Starter Kit!

Sign up for the NGB Monthly Newsletter & you'll get a FREE downloadable PDF with Russian language and travel resources for your post-Soviet journey!

оставаться на связи