The History of the Baltics Pre-USSR: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania

After a long break from travel due to COVID-19, I was finally able to return to the former Eastern bloc in winter 2022 and travel around the Baltic countries – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania! Although my primary interest lies in Soviet history, it proved too difficult to just ignore the plethora of medieval castles and fortresses that fill the region simply because they predate the USSR. So I decided to dive head first into the pre-Soviet history of the Baltics and visit all the historical spots I could. Afterall, in order to get a full picture of Soviet influence in the Baltics, it is important to understand the history of the region and context for why events unfolded as they did. For this, we need to go back in time – And what better place to start is there than the beginning?

The information from this article is an amalgamation of information I learned as I went through several museums throughout Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. These include the Estonian History Museum located in Maarjamäe Palace (Tallinn, Estonia), the National History Museum of Latvia (Riga, Latvia), the National Museum at the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania (Vilnius), and the museums inside the Kuressaare Castle (Saaremaa, Estonia), Haapsalu Castle (Haapsalu, Estonia), Cēsis Castle (Cēsis, Latvia), Turaida Castle (Sigulda, Latvia), Castle Of The Livonian Order In Sigulda (Sigulda, Latvia), and Trakai Castle (Trakai, Lithuania). Additionally, where I was missing pieces I used internet resources to fill the gaps – these are cited at the bottom of the article.

Last updated: 1/28/23

Contents

- Prehistory – 12th Century

- The Livonian Crusade

- The Rise of Lithuania

- The Decline of the Livonian Order & Conflict within the Livonian Confederation

- The Livonian War (1558-1583) & The Formation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

- The Polish-Swedish Wars

- The Second Northern War (1655-1660)

- The Great Northern War (1700–1721)

- The Partition of Lithuania, 1772-1795

- The Russian Empire Takes Over the Baltics

- Works Cited

Pre-Soviet History of the Baltics

Prehistory – 12th Century

The first inhabitants of today’s Baltic region consisted of Finno-Ugric tribes who migrated to the northernmost part around the 12th century BC. During the Neolithic Period (10,000 BC-2200 BC), Indo-European Balts followed them, and put down their roots in the southern part of the region. By the Late Iron Age (1200 BC-500 BC) loose political organizations between the tribes in these regions began to form and establish trade relations with groups in nearby regions.

Over the next several centuries, pressures from the east and west solidified bands of tribes and local languages. Grouping together gave tribes the ability to protect themselves from foreign raids, tributary demands, and other territorial incursions.

In the north, the coastal area hugging the Gulf of Riga was home to a group called Livonians. Livonians, or “Livs,” were close linguistic relatives of present-day Estonians and differed not ethnically from their southern neighbors, but culturally. This cultural difference would play a large role in shaping the modern Baltic countries today. The tribes that occupied modern-day Latvia were known as the Latgalians, Semigallians and the Selonians. The Curonians occupied the western coastal stretch of land which is part of modern-day Latvia and Lithuania. And finally, two main groups that consisted of several tribes would come to constitute early Lithuanians: the Samogitians, or “Lowlanders”, and the Aukštaitijai, or “Highlanders.” The Prussians, Scalvians, and Yotvingians were closely related tribes that inhabited the modern-day areas of the Russian oblast of Kaliningrad and north-eastern Poland. However, because there were no unified political states in the Baltics at the time, Christianity was slow to make its way to the area, leaving its residents susceptible to attack and enslavement by several groups over the next few centuries such as the Vikings and principalities of the Kievan Rus’.

The Livonian Crusade

German knights of the Teutonic Order swept into Estonia as part of the Livonian Crusade – a military offensive against the pagan people of Livonia (modern-day Estonia and Latvia). The city of Riga, which was founded by Germans in 1201, became a key base for the knights and fought at the direction of Pope Innocent III to spread Christianity and take control of the lucrative trade routes. The German crusaders prevailed in southern Estonia and established a principality of the Holy Roman Empire called Terra Mariana.

Terra Mariana was ruled by the Livonian Order starting in 1237, a semi-autonomous, junior partner of the Teutonic Knights. In the north of Estonia, the Kingdom of Denmark, who was also a belligerent force in the Livonian Crusade, seized control and formed the Duchy of Estonia. Dutch rule in the north was short-lived, however, and after a slew of costly rebellions, the Danes sold their land in Estonia to the Germans of the Livonian Order in 1346. These Germans, now referred to as the “Baltic Germans,” thus established total control over modern-day Estonia. Although they only constituted around 4% of the population, Baltic Germans formed the local elite and would rule over the rural Estonians through their network of manorial estates until the end of the 19th century.

The Rise of Lithuania

Leading up to the Livonian Crusade, Lithuanians, like their Baltic neighbors, were forced to pay tribute to Kievan Rus’ and were subject to frequent raids (Plakans, p. 14). But unlike Livonians, Lithuanians managed to successfully band together (i.e. conquer neighboring tribes) and form an organized military force. This plus their location in the dense forests and wetlands allowed Lithuanians to push back against invading forces, and ultimately resist the Teutonic Order.

The Lithuanian figure credited with the consolidation of the numerous pagan Baltic tribes into a state is called Mindaugas. He became the first – and only – King of Lithuania in 1253, during which he was baptized Roman Catholic. This conversion made possible a brief political alliance with their hostile neighbor to the north – the Livonian Order. During his reign, Mindaugas used a combination of brutal force and strategic marriages to expand Lithuania’s borders. Consequently, Mindaugas and his entire family was murdered in 1263, bringing Lithuania’s status as a kingdom to an end.

The period after Mindaugas’ murder was rife with turmoil and a renewed fear of foreign invasion from the Teutonic knights. The next series of rulers who took power would continue the quest to unify more Baltic tribes and expand their borders under the name of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the early 14th century, Grand Duke Vytenis made a name for himself through his diplomatic efforts and numerous military campaigns against the Teutonic Knights. He created alliances with the archbishop and bourgeoisie of Riga which would later make possible significant border expansion in the 14th and 15th centuries. Vytenis’ death led to the accession of his brother, Gediminas, as the Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1316. He established the Gediminid dynasty which would hold power in Poland and Lithuania for the next two centuries. His primary goals included staving off the persistent threat from the Teutonic Knights, expanding Lithuania’s territory to the southeast, and ensuring Muscovy from becoming a powerful enemy. Through strategic diplomacy, Gediminas played a key role in bringing Lithuania to the main stage of European politics. Gediminas was responsible for fortifying and expanding upon the castle whose ruins are on display at the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania in Vilnius today.

After his death in 1341, Gediminas’ son Algirdas, took the throne, envisioning unifying the Slavic lands previously ruled by the now-dissolved Kievan Rus’. His vision, however, was made difficult by the growth in power of Muscovy and the emergence of the Golden Horde. Despite several unsuccessful attempts to take Moscow between 1368-1372, Algirdas did manage to extend the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s borders considerably to the southeast by annexing Kiev, Tver, Vitebsk and other Russian principalities. After a brief succession crisis, Algirdas’ son, Jogaila, became the Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1377 and then married the daughter of the king of Hungary and Poland, Jadwiga, thus offering Jogaila the throne to the Kingdom of Poland in 1386 (“WHKMLA : History of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania”). After becoming baptized as Władysław II Jagiełło, and thus founding the Jagiellonian dynasty, Lithuanian and Polish armies were combined which would later pose a major threat to the rule of the German Teutonic Knights in Livonia. Moreover, after Grand Duke Jogaila converted Lithuania to Catholicism in 1387. The Teutonic Knights lost their pretext to occupy the lands as the “defenders of Christianity” against paganism in the region (“WHKMLA : History of the Teutonic Order, 1409-1525”). Jogaila’s rule not only ushered in the Christianization of Lithuania, the last pagan country in Europe, but also granted Vilnius Magdeburg rights (rights for self-governance). Jogaila successfully built the foundations of the political state of Lithuania, and gave way for Vilnius to become its legislative, cultural, and military center.

Although Jagiełło initially appointed his brother, Skirgaila, to serve as the regent of Lithuania, he would later be replaced in 1392 by Vytautas “the Great ” who is considered to be Lithuania’s most consequential ruler. Polish-Lithuanian armies finally managed to defeat the Teutonic Order in 1410 at the Battle of Grunwald, eliminating the thorn in Lithuania’s neck going back centuries (“Lithuania (11/18/11)”). Under Vytautas’ rule, Lithuania saw its largest ever border expansion, extensive economic and educational reforms, and further efforts to spread Christianity throughout the empire. He also saw the passages of the Union of Horodlo in 1413 which granted Lithuania more autonomy by allowing Lithuanian nobles the ability to choose Vytautas’ eventual successor, with the approval of Poland of course, and have veto power in the selection of a new Polish king. This resulted in a stronger cultural, political and social union between Lithuania and Poland.

The Decline of the Livonian Order & Conflict within the Livonian Confederation

The Battle of Grunwald in 1410 marked the beginning of the Teutonic Order’s decline, but the Livonian Order managed to make a truce with Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas and survive since it did not participate (Christiansen, Eric). However, the Livonian Order would be similarly brought to its knees following its participation, and eventual defeat, in the Battle of Wiłkomierz in 1435 as part of the Lithuanian Civil War. The Livonian Confederation was established in 1435 after the Livonian Order’s defeat in the Battle of Wiłkomierz and consisted of the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order, the prince-bishoprics of Dorpat (now “Tartu”), Ösel–Wiek, Courland, the Archbishopric of Riga and the city of Riga.

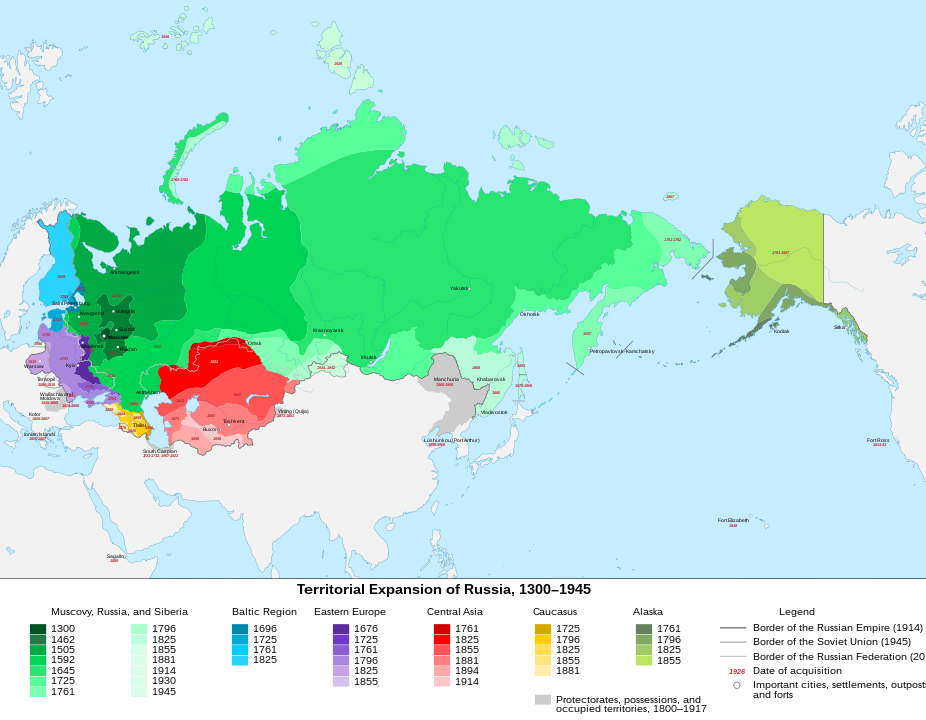

Notwithstanding the religious divide between Catholic Livonia and its Orthodox neighbor to the east, the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the two states enjoyed fairly peaceful and mutually-advantageous trade relations (Kristjan Kaljusaar). However, as Muscovy rose in prominence, the Livonian princes who enjoyed the power and wealth they had, began to portray Muscuvy as a boogeyman figure that was growing too fast for Livonia’s own comfort. Especially since the Golden Horde’s power over Muscovy came to an end in 1480 and Ivan III began to exponentially expand Muscovy’s territory, tensions between the Catholic and Orthodox powers finally came to a head in a Livonian-Muscovite war ending in 1503 with a truce. The German Teutonic Knights, holding on by a thread at this point, intended to make this truce short-lived and, in the meantime, drum up support among the greater Livonian Confederation. This support would not materialize, however, especially after the Protestant Reformation spread from Germany to the, now-called, Livonian Confederation, in the 1520s.

Internal conflict between the member states of the Livonian Confederation hit a breaking point after Albrecht von Hohenzollern, a German prince and a former Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, turned against his Catholic roots and converted to Lutheranism in 1525 as part of the Treaty of Kraków which ended the Polish–Teutonic War of 1519–21. Additionally, von Hohenzollern officially declared himself the Duke of Prussia with the approval and oath of allegiance to his uncle Sigismund I, the King of Poland. The new Duke of Prussia could, of course, not preside over a Catholic land, so he immediately secularized all the Prussian territory formerly ruled by the Teutonic Order (“WHKMLA : History of Livonia”). This now meant that the Teutonic Order’s northern branch within the Livonian Confederation became even more isolated and had to manage on its own. At first, however, this wasn’t all bad news for Livonia. Tallinn rejoiced and, for a few decades, the Livonian Confederation enjoyed relatively peaceful times without foreign invasions. The Baltic Germans in the Livonian Confederation gradually adopted and promoted Lutheranism, further dividing support for the Teutonic Knights, and all aspects of society were transformed, including the printing of the first texts in Estonian rather than Latin, thus making it more accessible to the local Estonian population.

The Livonian War (1558-1583) & The Formation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Increasing tensions between the Livonian Order and the Archbishop of Riga, another member of the Livonian Confederation, resulted in an armed conflict which weakened the region and made it vulnerable to foreign invasion.

This presented an opportunity that the Livonian Confederation’s eastern neighbor was all too happy to capitalize upon. Grand Prince of Moscow, Ivan IV, declared war on the Livonian Confederation in 1558 and invaded the modern-day eastern Estonian cities known as Narva and Tartu. This became known as the Livonian War, or the First Northern War. Cities were left largely defenseless because the Hanseatic League that had previously enjoyed a monopoly on the Baltic Sea trade was now one of several competing forces in the region. Consequently, it could no longer maintain its previously strong navy to protect Livonian cities such as Riga, Tallinn, and Narva. Moreover, the infighting and refusal of Baltic German elites to arm the peasants for fear of uprisings meant that Ivan IV’s military forces quickly overpowered Livonia’s (“History – Virtual Livonia”). With no means to defend itself, the Livonian Confederation officially dissolved with the Treaty of Vilnius in 1561.

In addition to the Tsardom of Muscovy, Livonia’s neighbors were also eyeing the strategically located territory, and many decided to put their hat in the race and enter the conflict as well. Before the Livonian Confederation ceased to exist, its leaders had turned to Poland-Lithuania for protection and signed a defense agreement in 1559. Thus, Polish-Lithuanian military forces entered the conflict and largely pushed the Russian forces out of Livonia. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was now in control of the majority of land previously part of the Livonian Confederation (“A Brief History of Latvia”). This territory became a vassal state to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania called the Duchy of Livonia. In the north of Estonia, Tallinn had asked the Kingdom of Sweden for assistance, and would then come under Swedish rule in 1561 (“WHKMLA : History of Swedish Estonia”). Starting in 1561, this territory was known as the Duchy of Estonia. In the west, the territories previously under the Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek of the Livonian Confederation, including the large island of Saaremaa, were sold to Frederick II of Denmark in 1560 who then made it into a duchy for his brother, Magnus of Holstein. The Danish Duke Magnus of Holstein would go on a decade later to be crowned “King of Livonia” by Russian Tsar Ivan IV after signing a treaty to set up the contested territory of Livonia as a vassal state of the Tsardom of Russia. The territory hadn’t yet been conquered, but those were just minor details to be sorted out later apparently. When the “later” came the following year and Magnus led 20,000 Russian troops into Tallinn, he would flee the battle unsuccessful. In 1569, the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania merged into one state called the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth through the Treaty of Lublin which significantly increased its strength in the region (“WHKMLA : History of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth”). After Stephen Báthory was elected the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, he launched a counteroffensive against Russia which expelled all Russian troops out of Livonia and turned Russian soil into a battleground from 1578-1581. The Livonian War concluded after Báthory and Ivan IV signed the Treaty of Yam-Zapolsky in 1582 and the Treaty of Plussa was signed the following year in 1583 between Russia and Sweden. There is no general consensus among scholars on the categorization of wars in Livonia and the greater Baltic region during this time. For the purpose of this article, we will use the lens provided by Robert Frost as described in his book War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558 – 1721. Frost posits that the Northern Wars consist of three major conflicts, the first of which being the Livonian War.

The Polish-Swedish Wars

The period after the end of the Livonian War would see the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Kingdom of Sweden come into conflict on-and-off for several decades. One inciting incident for the series of wars to come was a marriage between elites in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Kingdom of Sweden which resulted in Sigismund Vasa being elected as King of Poland in 1587 and then inheriting the Swedish crown in 1592. His Catholic upbringing did not resonate well with the Protestant people of Sweden, and in 1598, Sigismund’s uncle led a successful uprising against him (“WHKMLA : History of Livonia, 1561-1621”). The two kingdoms would wage war over who had legitimacy over the Swedish throne and territorial disputes between the then-Swedish ruled Duchy of Estonia and former Livonian land incorporated into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. These wars, separated by periods of stalemates, included the Polish-Swedish War of 1600–1611, 1617–1618, 1621–1625, and 1626–1629 (“Swedish-Polish War, 1620-1629”). By 1629, Sweden was the definitive victor, and gained much of Livonia, the right to tax Polish trade through its territory, and control of nearly all of the Baltic sea ports.

The Second Northern War (1655-1660)

After Swedish victory in the Polish-Swedish Wars and in the recently resolved Thirty Years War (1618-1648), Sweden’s power was steadily on the rise, while the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was facing internal strife that presented a weakness on the international stage (Dyer, pg. 520). Sweden and the Tsardom of Russia smelled blood in the water, and used the moment to advance into largely undefended Polish-Lithuanian territory. Russia was the first to strike in 1654 after winning the allegiance of the local Cossacks who had staged the Khmelnytsky Uprising in 1648 (which had been one of the major events to weaken the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the first place). This incursion by Aleksey Mikhaylovich, the Tsar of Russia from 1645-1676, marked the start of the Russo-Polish War (1654–1667), also known as the Thirteen Years’ War, which fought over control of the Commonwealth’s eastern territory, modern-day Ukraine and Belarus (“WHKMLA : History of the Russian Empire, 1547-1917”). After seeing Russia’s success in its campaign against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, King Charles X, the King of Sweden from 1654-1660, decided to throw his hat into the race as well invading the western portion of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1655, claiming to do so in defense of the Protestants residing there. Initially, Sweden won several victories such as taking control of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (despite the merger of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had maintained independent ministries, laws, military units, and its treasury), forcing the Polish King John II Casimir Vasa to flee to the Habsburgs, and securing the support of Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia, who had previously been loyal to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. The matter of religion – specifically Swedish Protestantism vs. Polish-Lithuanian Catholicism- still remained a contentious issue that allowed John II Casimir Vasa to regain support and land in territories that had recently been captured by Sweden.

When the tides of war quickly changed for Sweden, Russia took advantage of its temporary truce with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden’s setback by declaring war in 1656. Russia then advanced into Swedish Livonia and Lithuania which began the Russo-Swedish War (1656–1658). Russia was not successful in its conquest to regain territory lost as a result of the Treaty of Stolbovo – the treaty in which Russia renounced all claims to Estonia and Livonia, which marked the end of the Ingrian War (1610-1617). This was mostly because the Ukrainian Cossacks realigned themselves with Poland, and Russia felt compelled to resume war with Poland.

The major players in the Second Northern War were not limited to Sweden, Russia, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Throughout the conflict, several European powers were drawn in as allies with the promise of eventual spoils of war, and additional regional powers struck the primary combatants while the iron was hot in the hopes of settling old scores. But by February 1660, the fighting came to a halt with the signing of the Treaty of Oliva between Sweden and Habsburg, Brandenburg, and Poland–Lithuania. Sweden was ultimately unsuccessful in claiming Polish-Lithuanian land, and was forced to withdraw from all occupied territories. The truce between Sweden and Russia from 1658, which acknowledged Sweden’s claim to territory gained in the Treaty of Stolbovo, was then cemented with the Treaty of Cardis in 1661.

The Great Northern War (1700–1721)

After Charles XI’s death in 1697, his only son, Charles XII, rose to the throne at the ripe old age of 15. Sweden’s neighbors saw this as an opportunity to kick the Swedish Empire out of the Baltics once and for all and began to strategize over what would now be called the Great Northern War, or the Third Northern War. Sweden’s enemies – new and old – formed a strategic alliance consisting of Tsar Peter I of the Russian Empire, Frederick IV of Denmark-Norway, and Augustus II of Saxony and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. They declared war and launched a three-front attack on Sweden in 1700. Newly crowned Charles XII quickly put down the Danish advance in the west and forced Frederick IV out of the war in a matter of months. This allowed Charles XII to send troops over to the eastern Estonian city of Narva where Peter I had laid siege. Sweden managed to not only stop the Russian incursion in Narva, but then managed to launch a counter-offensive against Augustus II through the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth all the way to Saxony. Charles XII forced Augustus II to renounce his claim to the Polish throne and admit defeat in the Treaty of Altranstädt in 1706.

During this time, however, Peter I’s army recovered from their initial loss in Narva and managed to establish the city of Saint Petersburg in 1703 which strengthened its military position. Swedish forces tried to refocus their attention on fighting Russia and invaded in 1707, but were ultimately defeated in the Battle of Poltava in 1709. Peter I then took Tallinn in 1710 (“The Legacy of the Russian Empire in the Baltic Provinces”). Charles XII was exiled to the then-Ottoman ruled Bender, a town in modern-day Moldova, as a result. This Swedish defeat reinvigorated the previous anti-Swedish alliance members to resume fighting, with Hanover and Prussia also joining the coalition. The Great Northern War officially ended following the Swedish-Hanoverian and Swedish-Prussian Treaties of Stockholm (1719), the Dano-Swedish Treaty of Frederiksborg (1720), and the Russo-Swedish Treaty of Nystad (1721). The Treaty of Nystad ceded all of the Swedish Empire’s Baltic territory to the Russian Empire including Swedish Livonia, Swedish Ingria, Swedish Estonia, and Finland.

The Northern Wars hold great significance in relation to not only the fate of Livonia, but also the power dynamics of feuding empires in the greater Baltic region as well. The conclusion of the Great Northern War in 1721 signifies the sunset of Swedish autonomy in the Baltics, the diminishing role of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the rise of the Russian Empire as the major regional player. (Frost, Robert I.: The Northern Wars: War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558-1721. Routledge: New York, 2000, p. 13). Modern-day Estonia and Latvia were now part of the Russian Empire.

The Partition of Lithuania, 1772-1795

In addition to the devastations of the Great Northern War, the Commonwealth also had to contend with famine and plague. The combination of these tragedies resulted in the death of 40% of its population, further bringing the Commonwealth into decline. The Russian Empire began chipping away at the Commonwealth through the Partitions of Lithuania from 1772-1795. In their final attempt to preserve statehood, Lithuanian and Polish forces launched the Kościuszko Uprising. The uprising ended in defeat, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth officially ceased to exist in 1795. The Russian Empire was now in control of most of modern-day Lithuania, including Vilnius.

The History of the Baltics From the Russian Empire

So I will end this article with the Russian Empire’s expanse into the Baltics. I hope this article gave you a better idea of how the individual Baltic countries came to be, because this will set the stage for the events to come in the 19th and 20th centuries. The articles to follow this one will be individual history articles for each of the Baltic countries and their respective experiences as they go from being part of the Russian Empire, to brief periods of independence, to Soviet occupation. After all, that is the focus of this blog!

If you have any questions or corrections, please leave a comment below! Also below are the souces cited in this article. See you next time.

Works Cited

“A Brief History of Latvia.” Latvians.com, 2023, latvians.com/index.php?en/CFBH/AShortHistory/Short-000-hist.ssi.

Christiansen, Eric. “The Northern Crusades”. (1997) Penguin. p. 111. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

Dyer, Thomas Henry. “The History of Modern Europe, from the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the War in the Crimea in 1857”. United Kingdom, J. Murray, 1861.

“History – Virtual Livonia.” Virtual Livonia, 2017, virtuallivonia.info/?page_id=130.

Kristjan Kaljusaar. “The Teutonic Order in Medieval Livonia.” Tallinn Museum of Orders of Knighthood, 13 Oct. 2018, tallinnmuseum.com/2018/10/13/the-teutonic-order-in-medieval-livonia/.

“The Legacy of the Russian Empire in the Baltic Provinces.” Rem33.com, 2016, www.conflicts.rem33.com/images/The%20Baltic%20States/russian_rule.htm.

“Lithuania (11/18/11).” U.S. Department of State, 2017, 2009-2017.state.gov/outofdate/bgn/lithuania/191349.htm.

Plakans, Andrejs. The Latvians: A Short History. Hoover Institution Press, 2008.

“Swedish-Polish War, 1620-1629.” Www.zum.de, 2023, www.zum.de/whkmla/military/17cen/swedpol16201629.html.

“WHKMLA : History of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.” Www.zum.de, 2023, www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eceurope/xgdlithuania.html.

“WHKMLA : History of Livonia.” Www.zum.de, 2023, www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eceurope/xlivoniapol15611621.html.

“WHKMLA : History of Livonia, 1561-1621.” Www.zum.de, 2023, www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eceurope/livonia15611621.html.

“WHKMLA : History of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.” Www.zum.de, 2023, www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eceurope/xrzeczpospolita.html.

“WHKMLA : History of the Russian Empire, 1547-1917.” Www.zum.de, 2023, www.zum.de/whkmla/region/russia/xrusempire.html.

“WHKMLA : History of Swedish Estonia.” Www.zum.de, 2023, www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eceurope/xswestonia.html.

“WHKMLA : History of the Teutonic Order, 1409-1525.” Www.zum.de, 2023, www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eceurope/teutord14.html.

Learn to speak russian

Travel with ease & dive into the culture, history & lifestyle of post-Soviet countries

free russian learning materials

Melissa

Get the Goods

Head over to the Language & Travel Shop to check out my favorite goodies I use for learning Russian and traveling! I've compiled all my favorite products I use when #onthebloc so that you can benefit from them when you travel abroad. Help yourself prepare and support this blog at the same time :) Счастливого пути!

carry-on goods

gifts for travelers

photography

apparel & accessories

textbooks & readers

luggage & bags

categories

#oTB essentials

Russian-Speaking Travel Destinations

use your new russian skills in real life!

Belarus

EASTERN EUROPE

central Asia

central Asia

Eurasia

Russia

Kyrgyzstan

armenia

Moldova

Kazakhstan

eastern europe

read »

read »

read »

read »

read »

read »

The caucasus