The History of Latvia under the Soviet Union

In winter 2022, I was fortunate enough to travel the Baltic countries and get a deep dive into their histories. After writing about The History Of The Baltics Pre-USSR: Estonia, Latvia And Lithuania, it only seems natural to continue the series with the history of Latvia under the Soviet Union. This article will detail Latvia’s history from the Viking’s introduction to the region in the 9th century to the fall of the Soviet Union and Latvia’s subsequent independence in 1991.

The information from this article is a mix of information I complied as I went through several museums throughout Latvia. These include the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia (Riga, Latvia), the National History Museum of Latvia (Riga, Latvia), Cēsis Castle (Cēsis, Latvia), Turaida Castle (Sigulda, Latvia), and Castle Of The Livonian Order In Sigulda (Sigulda, Latvia). Additionally, where I was missing pieces I used internet resources to fill the gaps – these are cited at the bottom of the article.

Last updated: 6/23/23

Contents

- Early History of Latvia

- Latvia under the Russian Empire

- World War I & the Fall of the Russian Empire

- Latvian War of Independence (1918-1920) & Latvia’s Parliamentary Era (1920-1934)

- Kārlis Ulmanis’ Coup & Dictatorship (1934-1940)

- The “Latvian Operation” of the Soviet NKVD

- The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact & The USSR’s Annexation of Latvia

- Latvian Resistance to Soviet Rule & Soviet Mass “June Deportation” of 1941

- Nazi Invasion of Latvia in 1941 & the Holocaust in Latvia

- The Soviet Army’s Return to Latvia in 1944 & Latvia Behind the Iron Curtain

- Partisan Forest Fighters & Operation “Pribori”

- Latvian Resistance to Soviet Occupation

- Latvians and the GULAG

- The Death of Stalin & The Thaw

- “Homo Sovieticus”

- Latvia in the Cold War

- The Third Latvian National Awakening & Latvian Independence

- Works Cited

The History of Latvia & the Soviet Union

Early History of Latvia

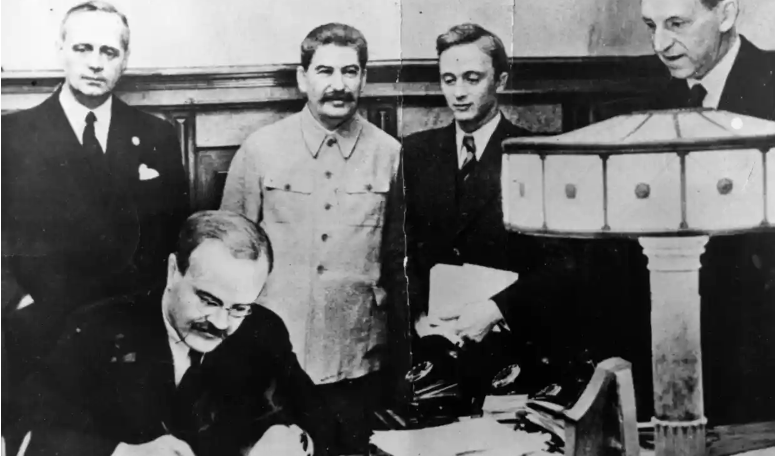

Latvia was initially inhabited by the ancient Balts. In the 9th century, the Balts came under the rule of the Varangians, also known as the Vikings. However, a more enduring dominance in modern-day Latvia was established by the German Teutonic Order as part of the Holy Roman Empire’s Livonian Crusade in 1230. The Teutonic Order established in Latvia the tenants of medieval society including Christianity and the feudal system. During this time, Latvia became part of what was known as Terra Mariana, or Medieval Livonia. From the 13th-16th centuries, Medieval Livonia (called the Livonian Confederation following the Teutonic Order’s decline in 1410) remained under German control.

The feudalistic arrangement in place was far from harmonious, given the constant disputes among its three main components: the Teutonic Order, the archbishopric of Riga, and the free city of Riga. Additionally, due to vulnerable borders, the confederation found itself engaged in frequent foreign conflicts. However, there were some advantages for the Latvians when Riga joined the Hanseatic League in 1282, as trade within the league brought prosperity to the region. New fortified cities with stone castles sprang up during this time and became hubs for marketplaces and trading centers. Nevertheless, the overall situation for the Latvians under German rule mirrored that of other subjugated nations. The native nobility was largely extinguished, with only a few members changing their allegiances, and the rural population was compelled to work for and pay taxes to their German conquerors.

In the north, the coastal area hugging the Gulf of Riga was home to a group called Livonians. Livonians, or “Livs,” were close linguistic relatives of present-day Estonians and differed not ethnically from their southern neighbors, but culturally. This cultural difference would play a large role in shaping the modern Baltic countries today. The tribes that occupied modern-day Latvia were known as the Latgalians, Semigallians and the Selonians. The Curonians occupied the western coastal stretch of land which is part of modern-day Latvia and Lithuania. And finally, two main groups that consisted of several tribes would come to constitute early Lithuanians: the Samogitians, or “Lowlanders”, and the Aukštaitijai, or “Highlanders.” The Prussians, Scalvians, and Yotvingians were closely related tribes that inhabited the modern-day areas of the Russian oblast of Kaliningrad and north-eastern Poland. However, because there were no unified political states in the Baltics at the time, Christianity was slow to make its way to the area, leaving its residents susceptible to attack and enslavement by several groups over the next few centuries such as the Vikings and principalities of the Kievan Rus’.

In the 16th century, Latvia was introduced to the Protestant Reformation, which had a significant impact on the country’s religious and cultural life. Lutheranism became the dominant religion, and many churches and monasteries were closed down or converted, resulting in the Teutonic Order’s increasing decline. Society became further split as new divisions in society dictated who worked for whom. Most of the locals were peasants who worked the lands of the local fief men, or land holders. This all changed, however, after the Russian Grand Prince of Moscow, Ivan the Terrible, launched the Livonian War in 1560. Although Russia was ultimately unsuccessful in its campaign, the Russian army did manage to weaken the Livonian army enough for the Livonian Confederation to submit to the Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland. This marked the end of the Livonian Confederation. Latvia, then as the Duchy of Courland and the Duchy of Livonia, then came under the control of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which brought with it new administrative systems and religious reforms.

In the early 17th century, Sweden gained control of Latvia and established a new administrative system. Under Swedish rule, Latvia experienced a period of stability and prosperity, with the development of trade, agriculture, and education.

Latvia under the Russian Empire

The rulers of the Grand Principality of Muscovy had made unsuccessful attempts to reach the Baltic shores of Latvia in the past. Ivan III and Ivan IV had both tried, and the Russian tsar Alexei continued these efforts in his wars against Sweden and Poland from 1653 to 1667. It was not until Peter I during the Second Northern War that Russia succeeded in gaining access to the Baltic Sea. In 1710, Riga was captured from the Swedes, and under the Treaty of Nystad in 1721, Russia secured control over Vidzeme. Latgale was annexed by the Russians during the First Partition of Poland in 1772, and Courland was acquired in the Third Partition in 1795, effectively placing the entire Latvian territory under Russian rule by the end of the 18th century.

As part of the Russian Empire, Latvia saw the establishment of serfdom, a system of feudal labor relations that tied peasants to the land. Serfdom had a significant impact on the country’s social and economic development and lasted until the 19th century. In the late 18th century, Latvia became exposed to the Enlightenment, a cultural and intellectual movement that emphasized reason, science, and individual liberty. The Enlightenment had a profound impact on Latvian culture and helped pave the way for the country’s eventual independence.

During the 19th century, Latvia experienced a period of significant changes in its religious, political, and social structure. Early in the century, Latvians began to develop a sense of national identity and pride, leading to a movement known as the “National Awakening.” This movement sought to promote Latvian culture, language, and traditions and played a significant role in the country’s eventual independence. However, in the latter half of the century, Latvia came under increasing pressure from Russian authorities to adopt Russian Orthodoxy, the Russian language and culture. This policy of “Russification” was met with resistance by Latvians and contributed to growing tensions between the two groups.

Despite these challenges, Latvia underwent rapid industrialization, particularly in the areas of textiles, food processing, and metalworking. This led to a significant increase in urbanization and a shift away from the traditional rural way of life. By the end of the 19th century, Latvians had developed a strong sense of national identity and were increasingly calling for independence from Russian rule.

World War I & the Fall of the Russian Empire

Latvia was greatly impacted by World War I, which lasted from 1914 to 1918. At the outbreak of the war, Latvia was part of the Russian Empire and saw its young men drafted into the Russian army to fight on the Eastern Front. As the war dragged on, Latvia suffered from shortages of food and supplies, and the economy was heavily disrupted by the conflict. Latvia’s strategic location in the Baltic region made it a battleground during the war, with German and Russian forces fighting for control of the region. The front lines of the conflict shifted back and forth across Latvia, causing significant damage to the country’s infrastructure and towns.

The tumultuous era of World War I witnessed not only intense global conflict but also significant socio-political upheaval, setting the stage for the rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia. In 1917, the Russian Revolution led to the overthrow of the Russian monarchy and the establishment of a communist government in Russia. It consisted of two separate revolutions: the February Revolution and the October Revolution. The February Revolution, sparked by food shortages, war weariness, and discontent with the monarchy, resulted in the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the formation of a provisional government. However, dissatisfaction with the provisional government’s handling of the country’s problems paved the way for the October Revolution, led by the Bolshevik Party and its leader Vladimir Lenin. The Bolsheviks seized power, dissolved the provisional government, and established a socialist government known as the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. This marked the beginning of a new era in Russian history and ultimately led to the formation of the Soviet Union.

The collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 had a profound impact on Latvia and the outcomes of WWI. In March 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed between the new Bolshevik government of Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire) during World War I. It ended Russia’s participation in the war and acknowledged the independence of Ukraine, Belarus, and the South Caucasus. In return, Russia ceded large territories to the Central Powers, including parts of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and parts of Poland and Ukraine. The treaty was highly controversial and ultimately contributed to the Russian Civil War, as many Russians saw it as a betrayal of national interests. In Latvia, this resulted in the Courland and Livonian Governorates being given to the Germans. The Germans then quickly established an occupational regime, which remained in place until November 11, 1918.

On November 18th, 1919, The Latvian People’s Council, representing various groups such as peasants, bourgeoisie, and socialists, declared independence as the Republic of Latvia under the leadership of Kārlis Ulmanis. However, the newly independent Latvia faced significant challenges. The country was devastated by World War I and the subsequent Russian Civil War, which had spread into Latvia. In addition, the Bolsheviks, who had come to power in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917, did not recognize Latvia’s declaration of independence in 1918. The Bolsheviks viewed Latvia as part of the Soviet Union and saw the independence movement in Latvia as a threat to their plans for a unified socialist state.

Latvian War of Independence (1918-1920) & Latvia’s Parliamentary Era (1920-1934)

The Bolsheviks’ opposition to Latvia’s independence was part of a broader effort to maintain control over the former Russian Empire’s territories, which had become fragmented following the collapse of the empire. The Bolsheviks saw the Soviet Union as a successor to the Russian Empire and sought to bring all of its former territories back under Soviet control. As a result, in 1918, the Bolsheviks launched an offensive against the newly established Republic of Latvia, seeking to bring the country under Soviet control. The Latvian War of Independence ensued, which lasted from 1918 to 1920 and saw Latvian forces fighting against both the Bolsheviks and pro-Bolshevik Latvian groups. One such group was called the Red Latvian Riflemen – a pro-Bolshevik offshoot of the famous Latvian Riflemen.

The Latvian Riflemen were military units that originated during World War I within the Imperial Russian Army. The Latvian Riflemen played a significant role on the Eastern Front of World War I, participating in various battles against the German forces. They gained a reputation for their combat effectiveness and bravery in battle. After the Russian Revolution in 1917 and Latvia declared its independence in November 1918, the Latvian Riflemen became crucial in defending the newly established Latvian state during the Latvian War of Independence. However, while the majority of the Riflemen supported Latvian independence, some factions aligned themselves with the Bolsheviks and fought against the Latvian government, most notably, the Red Latvian Rifleman.

In the early stages of the war, the Red Latvian Riflemen controlled significant parts of Latvia, including the capital city, Riga. Their presence posed a significant challenge to the Latvian government and its allies, who sought to establish an independent Latvian state. However, as the war progressed, the Red Latvian Riflemen became divided in their loyalties. Some Riflemen started to question the Bolshevik cause and the dominance of Russian influence in Latvia. This led to a split within the Red Latvian Riflemen, with some factions siding with the Latvian government and the pro-independence forces. The turning point came in 1919 when the Red Army’s offensive in Latvia was repelled by a joint force of Latvian and allied troops. This defeat weakened the Red Latvian Riflemen’s position, and many of them either defected or joined the Latvian Army, fighting against their former comrades. Despite the odds against them, the Latvian War of Independence ended in 1920 with a decisive victory for the Latvian government and its allies.

After the Latvian War of Independence ended in August 1920, the newly established Republic of Latvia focused on building a stable and democratic government. The Constitutional Assembly elections were held on April 17-18, 1920 and, despite a significant decline in the population, with nearly a million fewer people, the elections saw a remarkable turnout of approximately 85% of eligible voters, as 50 party-lists and candidates vied for 150 seats. The Social Democratic Workers’ Party emerged as the largest party, securing 57 seats, followed by the Farmers’ Union with 26 seats and the Latgalian Peasant Party with 17 seats. This election set a precedent for future parliaments, characterized by the challenge of forming stable coalition governments due to the presence of numerous small interest-group parties.

Over the course of the parliamentary era from 1922 to 1934, Latvia witnessed 13 governments and 9 Prime Ministers. The passing of the Constitution of Latvia on February 15, 1922, and the subsequent Law on Elections in June paved the way for the formation of the Saeima, the national parliament. Four Saeimas were elected during this period: the 1st Saeima (1922-25), 2nd Saeima (1925-28), 3rd Saeima (1928-31), and 4th Saeima (1931-34). Latvia’s government prioritized economic development, seeking to rebuild the country’s infrastructure and stimulate growth. Efforts were made to modernize the agricultural sector and attract foreign investment to support industry and trade. The country also established diplomatic relations with other countries, including the United States, which recognized Latvia’s independence in 1922.

Kārlis Ulmanis’ Coup & Dictatorship (1934-1940)

In 1934, Prime Minister Kārlis Ulmanis and Minister of War Jānis Balodis, both considered fathers of Latvian independence, staged a coup and took control of the Latvian government. The coup saw the suspension of Parliament and the Constitution, the implementation of a State of War, the banning of all political parties, labor unions, and other civic organizations. The press became highly censored and controlled, and many journalists and writers were arrested and imprisoned. Ulmanis’ dictatorship was thereby characterized by strict control over civil liberties and political freedoms.

During his rule, the Ulmanis regime largely implemented policies to promote Latvian nationalism and culture, but this was done at the expense of minority rights. The regime suppressed the use of minority languages and forced minorities to adopt Latvian names. As with most other industries during his rule, the economy was also heavily regulated under Ulmanis. The government controlled prices and wages, and businesses were tightly controlled by the state. This led to a lack of innovation and entrepreneurship, which hindered economic growth.

In October 1936, Latvia achieved the honor of being elected as a non-permanent member of the Council of the League of Nations, a position it held for a period of three years. Following the glaring demonstration of the collective security system’s failure through the Munich Agreement, Latvia took decisive action on December 13, 1938, by proclaiming absolute neutrality in the brewing conflict of WWII. Subsequently, on March 28, 1939, the Soviet Union surprised Latvia by unilaterally announcing its interest in preserving and safeguarding Latvia’s independence, without engaging in any prior discussions. As international tensions continued to mount, Latvia and Germany signed a non-aggression treaty on June 7, 1939, aiming to ensure peaceful relations between the two nations.

The “Latvian Operation” of the Soviet NKVD

Ulmanis was quite eager to secure a non-aggression treaty with Latvia’s German neighbor to the west, especially since tensions with the Soviet Union had been escalating quickly over the previous few years. During the leadership of Josef Stalin, Latvia was viewed as an “enemy nation” and ethnic Latvians living in the Soviet Union became commonly labeled as “counter-revolutionary” and “suspicious elements”. Inside the USSR’s borders, over 500 Latvian peasant communities were established in the 19th century after serfdom was abolished, with many located near St. Petersburg, Novgorod, and Siberia. As of 1926, according to a census at the time, around 150,000 Latvians remained in the Soviet Union, where they established schools, newspapers, and theaters. Despite a strong Latvian presence in the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party since the 1905 Revolution and Latvian individuals holding high positions in the Soviet state apparatus, non-Russian minorities were gradually pushed out of management positions due to Russification efforts. Moreover, Latvian colonies within the borders of the USSR were specifically targeted for deportation to the Gulag, resulting in their complete elimination by 1933. Latvian cultural and educational societies faced forced closures and actors and employees of the Latvian theater “Skatuve” were executed. The Red Latvian Riflemen who had been a critical group in early support of the Bolsheviks were also removed from the USSR’s history books.

The persecution of Latvian nationals escalated heavily in 1937 with the implementation of the “Latvian Operation”. The “Latvian Operation” was a mass deportation and execution campaign carried out by the Soviet NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) in Latvia. On November 23, 1937, Nikolai Yezhov called on the NKVD to gather all intelligence on Latvians in cultural and political life, the military, and other public institutions. A week later, on November 30, Order No. 49990 was issued, titled “On carrying out an operation of repressing Latvians,” («О проведении операции по репрессированию латышей») which resulted in the arrest of thousands of Latvians throughout the Soviet Union. The legal process was swift with standardized accusations and fabricated confessions resulting from torture that resulted in sentences of labor camp detention or execution by firing squad. 22,360 Latvians were arrested on the grounds of anti-Soviet activities, espionage or insurrection between December 1937 and November 1938 – 16,573 would be given the death penalty for their “crimes.”

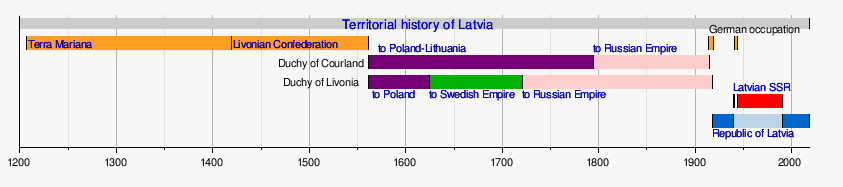

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact & The USSR’s Annexation of Latvia

As you may have likely guessed, the Soviet Union’s surprising announcement to respect Latvia’s autonomy in March 1939 was absolutely disingenuous. Less than six months later on August 23rd 1939, a non-aggression treaty called the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. The pact was named after the foreign ministers of the two countries, Vyacheslav Molotov of the Soviet Union and Joachim von Ribbentrop of Germany. Unbeknownst to the rest of the world, however, was a secret protocol that divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, with the Soviet Union being granted control over the Baltic states, Finland, and parts of Romania, while Germany was given a free hand to expand its influence in Western Europe.

Now knowing that Germany wouldn’t contest Soviet expansion into the Baltic theater, less than two months later, the Soviet Union used political pressure and military force to annex Latvia, as well as Estonia and Lithuania. In Latvia, this process began with Soviet demands for military bases in the country, which were granted by the Latvian government under pressure on October 5th, 1939.

On June 14, 1940, the Soviet Union issued another ultimatum to Latvia, demanding that the Latvian government allow more Soviet troops to enter the country to help “maintain order and protect the interests of the USSR.” The ultimatum was delivered by the Soviet ambassador to Latvia, who threatened military action if the Latvian government did not comply. The Latvian government was given just two days to comply with the ultimatum, and on June 16th the USSR falsely accused Latvia of breaking its 1939 neutrality treaty. Moscow used this as a pretense to demand that Latvia dissolve its government and allow an unlimited amount of Soviet troops to enter the country. Latvia was given 9 hours to capitulate or brace for Soviet military invasion. Although much of the reality of Soviet encroachment was not made public, Latvians could see the writing on the walls. That night, the Latgale Regional Song Festival was held in Latvia. As the festival came to an end, the festival-goers sang the national anthem of Latvia three times with tears in their eyes. The next day, hoping to protect Latvians from Soviet aggression if they didn’t agree to their demands, Latvia President Kārlis Ulmanis gave in to Moscow’s demands. Ulmanis was then arrested by the Cheka along with other members of the government, military officers, business owners and cultural workers.

The USSR, specifically Andrei Vishinski, the Deputy People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs, began to set the stage for Latvia’s annexation first by setting up a puppet government. Vishinski formed the “People’s Government” on June 19th, and installed Moscow-friendly Augusts Kirchenšteins as its head. In order to legitimize their invasion in the eyes of the people, Soviet officials drummed up artificial support for the regime, organized pro-Soviet demonstrations, and released all communists from prisons in Latvia. The new Soviet puppet government would then organize a parliamentary election in July 1940. Only candidates of the Working People’s Block, a political party created by the Soviet occupiers, were allowed on the ballots. Even before the election ended on July 15th, 1940, the results were published – 97.6% of the votes went to Working People’s Block candidates. The very first meeting of the “People’s Saeima,” the newly elected parliament, ended by declaring Soviet rule in Latvia and adopting a “Declaration on Latvia Becoming a Member of the Union of Socialist Republics.” On August 5th, 1940, Latvia was officially annexed by the USSR.

Latvian society was flipped on its head as the Soviet state system was imposed onto Latvia. After the USSR annexation of Latvia, a Soviet-style constitution was enacted. Businesses and private property were confiscated and the Latvian lats was replaced by the Soviet ruble, decimating many people’s life savings. All Latvian publications became censored and Communist ideology was forced into every sphere of daily life.

Latvian Resistance to Soviet Rule & Soviet Mass “June Deportation” of 1941

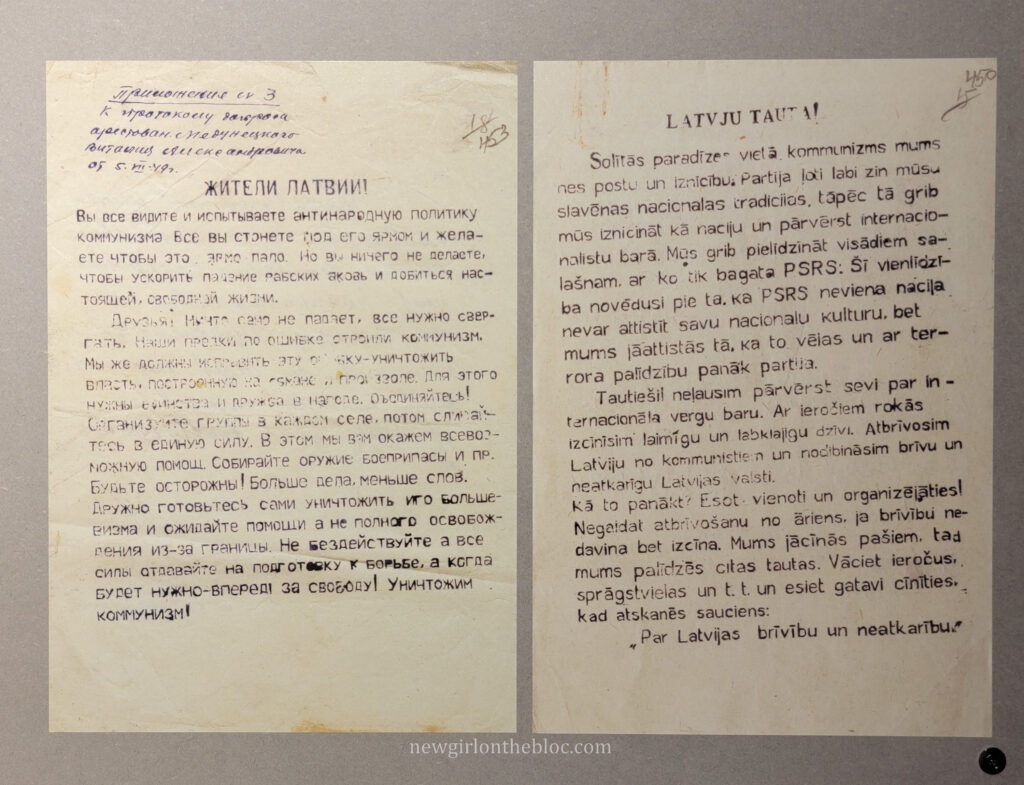

Resistance among Latvians came almost immediately following the Soviet annexation, especially from the younger generation. Secret resistance groups quickly formed such as Guards of the Fatherland, Young Latvians, the Latvian National Legion, and others, which worked to prepare for an armed rebellion to secure Latvian independence and distribute anti-Soviet leaflets around the country. Unfortunately, most of the members of such groups were arrested, and either executed or given hefty prison sentences.

In the middle of the night on June 13th, 1941, the Soviet Army arrested 15,443 Latvians and forced them into cattle cars bound for distant regions of the USSR. Upon deportation, fathers were then separated from their families and sent to gulags, while the women, children and elderly were forced to settle in Siberia. Deportees lost all their civil rights and were not allowed to leave the resettlement area. Conditions for deportees were primitive, and all lacked the basic necessities, food and medicine. Some even arrived to empty land where they were forced to dig-out shelters.

Nazi Invasion of Latvia in 1941 & the Holocaust in Latvia

After invading the USSR on June 22nd, 1941, Hitler’s army made its way to Riga and began its occupation on July 1st. While Latvians initially saw the Germans as liberators, the reality quickly set in that they weren’t any closer to regaining Latvian independence.

Life for Latvians dramatically changed once again as a result of their new occupiers. 20,000 Latvians were deported to Germany to work as laborers. Men were conscripted into the Waffen-SS, and thousands more were sent to concentration camps. Nazi ideology was forced upon Latvians, and Latvian Jews were forced to wear the Star of David. The German Security Police aimed to give the impression that increased antisemitic attacks came from local Latvians as a natural reaction to their “Jewish and communist” occupiers. The Nazis began the Holocaust in Latvia on July 4th, 1941, and within the span of only a few months would murder 70,000 Latvian Jews – 74% of Jews in Latvia. In total, Nazis murdered around 100,000 Latvians.

Latvians who were most adamant about achieving statehood placed their trust in the Western powers, namely Great Britain and the US. Despite their Nazi occupiers, representatives of major Latvian political parties founded the Latvian Central Council (LCC) in August 1943. The LCC worked to communicate with Latvian envoys abroad, draft memorandum for Western governments, and work with other Baltic organizations hoping to achieve similar goals of independence. LCC members also took it upon themselves to help Latvians escape to neutral countries, such as Sweden. They organized boats in conjunction with US and Swedish defense forces for refugees seeking shelter to use to cross the Baltic sea. This boat ride was extremely dangerous as both Nazi and Soviet forces were on alert to capture the boats and refugees on board.

LCC leadership was arrested by the Gestapo in spring 1944 and sent to the Stuttgof concentration camp. Resistance by the LCC continued, however, and even made its way to the army. In July 1944, General Janis Kurelis and his chief of staff, Captain Kristaps Upelnieks, got permission from the Nazi army to form a Latvian military unit intended to fight the Red Army. The General and his chief of staff, however, used this opportunity to restore an army for an independent Latvia and collaborated with the LCC. The 3,000 strong “Kurelian” army does not have a happy ending, unfortunately. Having uncovered their plot, the German SS captured Kurelis, executed his leadership, and sent about 2,000 of the unit’s soldiers to the Stutthof concentration camp. About 500 members, led by Lieutenant Robert’s Rubenis, managed to evade capture and engaged in several battles with the Nazis. The SS murdered 80 civilians in Zlēkas in retribution. Despite their leaderships’ arrests that spring and the Kurelian army failure, LCC members signed the “Declaration of the Renewal of Latvian Sovereignty” in fall of 1944, demonstrating their continuing resolve for independence.

The Soviet Army’s Return to Latvia in 1944 & Latvia Behind the Iron Curtain

Latvia became a battleground once again in July 1944 as the Soviet Army advanced against the occupying Nazi forces. All men in Latvia between the ages 16-37 were mobilized and sent to the Eastern front to fight the encroaching Red Army. Another horrible dimension of WWII for Latvians was the fact that Latvians who had been forcibly conscripted into the Red Army during the Soviet occupation were made to fight against the Latvians who were forcibly conscripted into the German army during Nazi occupation. During WWII, approximately 200,000 Latvians were compelled to serve in the German and Soviet armies, about half of whom would die. By the end of the war, Latvia lost 1/3 of its population between the thousands of deaths and those fleeing west.

150,000 refugees who fled to escape the war and then subsequent reestablishment of Soviet rule ended up in Germany, German-occupied territories, and Sweden by the end of 1944. Another 200,000 Latvians wound up displaced in Northern and Central Europe as prisoners-of-war, prisoners in concentration camps, and forced laborers.

After the Soviet return to power in Latvia, those who managed to survive the Nazi occupation of Latvia were often treated as collaborators, regardless if it was true or not. Around 200,000 soldiers were taken hostage by the Soviet army. Many Latvian soldiers, however, managed to escape to the forest where they would fight the Soviets as partisans. Latvian sources reported that Red Army units reintroduced themselves to Latvians by raiding villages, stealing all the food and animals they could find, raping the women, and shooting their automatic weapons indiscriminately out the windows as they left. Despite the end of WWII on May 8th, 1945, Latvia still found itself under occupation.

The triumph over Nazi Germany presented the wartime allies with a new question: Territorially, was this situation temporary, as the West believed, or was this the new world order as the Soviets saw it? The USSR’s military influence now spread over its occupied territories, all the way to the middle of Germany. The western powers became quite wary of this increased power balance. As such, the west worked to prop up democracy and capitalism in the former Nazi state. Increasingly hostile relations between the western and Soviet powers in their ideological conflicts led to the Baltic’s 40 year isolation behind what Churchill coined the “Iron Curtain.”

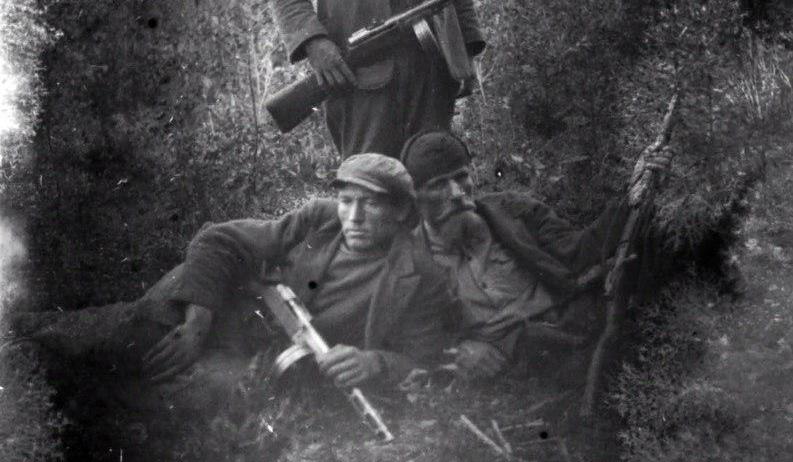

Partisan Forest Fighters & Operation “Pribori”

Despite the disappointment that came with yet another occupying force, Latvians did not take their Soviet occupiers lying down. The partisans who fled to the forests to fight the Soviets through guerilla warfare in the forests of Latvia and all around the Baltics hoped for Western assistance. In addition to fighting, they also spread anti-Soviet leaflets and newspapers around the townships they temporarily controlled. They regularly moved around to avoid Soviet detection and engaged in attacks on Soviet soldiers and infrastructure. The national partisan fighters enjoyed widespread support throughout the countryside as supporters assisted by supplying them with food and other basic goods, helping with communication, and hiding them when needed. The resistance the partisan fighters put up with the support of civilians, however, was not lost on the Soviets who knew this was hindering their ability to squash the resistance.

In March 1949, a second mass deportation known as Operation “Pribori” was executed in an effort to eradicate this growing resistance to Soviet rule. This deportation was aimed at removing the families of the national partisans, sympathetic countryside residents, and prosperous farmers known as “kulaks”. This proved helpful to the Soviets to speed up the collective farm system that many of these farmers had resisted. 43,125 Latvians were forcibly deported to various oblasts in Russia, 5,000 of whom perished while in exile.

In addition to the deportation of 1949, 25,000 Cheka and Red Army counter-intelligence agents worked together to eliminate the partisan “bandits.” They recruited local residents as informants, infiltrated partisan groups undercover, and threatened the family members of known partisans. The Soviets would also put slain partisans on display in the centers of townships to send a sinister message to its residents who were inclined to support the partisans.

Although the mass deportation in 1949 and Soviet counter-intelligence work reduced many of their supporters, national partisans continued their fight for independence against the Soviets. The last major battle between the national partisans and the Soviets happened a decade after the Soviets returned to Latvia in 1954, and the final partisans surrendered in 1957.

Latvian Resistance to Soviet Occupation

Resistance to Latvia’s Soviet occupants was not limited to the national partisans in the forests. Latvians engaged in their own non-violent forms of resistance such as spreading anti-Soviet leaflets, ripping up Soviet flags, observing national Latvian holidays, and collecting abandoned weapons. Unfortunately, the majority of clandestine youth organizations formed during this time were eliminated by the Cheka. Between 1944-1949, 740 Latvians under the age of 21 were arrested and 650 were convicted of their crimes. These kids were sentenced to up to 25 years in prison, the confiscation of property, and some were executed.

Another form of resistance that Latvians engaged in was consuming Western media and samizdat. Samizdat refers to the underground publishing and distribution of literature, typically critical or dissenting in nature, that was not approved or censored by the state authorities. It was a way for individuals and groups to express their views and circulate information that was not officially sanctioned. In Latvia, as in other Soviet republics, samizdat played an important role in the dissemination of alternative ideas and opinions that were suppressed by the Soviet regime. The Latvian samizdat movement was closely connected to the broader Soviet dissident movement, which emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. Despite the risks of persecution and censorship, Latvian writers and activists engaged in the production and distribution of samizdat literature to challenge the official Soviet narrative and promote freedom of expression.

It is worth noting that samizdat was an underground activity, and the materials produced were circulated within limited circles of individuals who were trusted to keep the information confidential. The Soviet authorities made efforts to suppress and persecute those involved in samizdat, considering it a threat to the state’s control over information. However, despite these challenges, the samizdat movement persisted and played a significant role in shaping public discourse and resistance against the Soviet regime in Latvia.

Latvians also engaged in resisting the Soviets from abroad. One example of this was the “Campaign of Light,” organized by Latvians in exile, who created a clandestine communication system designed to get accurate information about what was happening in the regime. Leaflets from this campaign encouraged its readers to give information about Latvians who were politically persecuted so they could shine a light on the terrible happenings under their occupiers.

Latvians and the GULAG

Between 1930-1988 the gulags held over 18 million criminals and political prisoners, 200,000 of whom were from Latvia. Daily life in the gulag was miserable – prisoners were forced to do hard labor with little food and subjected to terrible living conditions. In the winter, prisoners reported that the temperature inside their barracks fell to below freezing, and the rooms wreaked of toilet waste, smoke from the stove, and dirty clothes wet from sweat. The prisoners’ clothes were infested with fleas and lice, and bedbugs lived in the wall boards. The guards and criminals together terrorized political prisoners by stealing from them, attacking them, and murdering them every day. If gulag prisoners broke any rules, they were subject to solitary confinement, and the withholding of food and mail deliveries. Following WWII and the Soviet reoccupation of Latvia, the Red Army took 36,000 Latvian soldiers as prisoners of war. The prisoners were then sent to “filtration” gulag camps to verify their identity and their loyalty to the Soviet Union.

The Death of Stalin & The Thaw

After Stalin’s death in 1953, however, the narrative began to change. Khrushchev, Stalin’s successor, began the process known as “de-Stalinization” after his famous Secret Speech in 1956 in which he criticized Stalin’s repressions and cult of personality to the horror of much of the audience. This began a period known as “The Thaw,” during which those who had been sent to the gulags and survived were gradually released early and rehabilitated. Deportees who were forced to resettle for life in the USSR were suddenly allowed to return home. This presented new issues, however, as upon their return they were rendered homeless and drew heavy suspicion from the locals. They faced constant discrimination and harassment from the Soviet authorities to ensure their silence about what they endured in exile or the gulags. At the same time, however, Khrushchev’s thaw allowed for less restrictions on literature, culture and art which led to several famous publications being released by former prisoners.

“Homo Sovieticus”

Although many of the brutal tactics used by the Soviet regime during the Great Terror diminished after Stalin’s death, the totalitarian nature of the USSR did not. The Latvians continued to be subjugated, their Communist fate being centrally planned in Moscow and then handed down in Latvia. Elections in Latvia offered voters the choice of just one candidate per district chosen by the Communist party. During this time, the Soviet Union set about to fully assimilate the various satellite states in a campaign known as “Homo Sovieticus”. “Homo Sovieticus” refers to the concept of a “Soviet man” or “Soviet person” that emerged during the Soviet era to describe the ideal Soviet citizen who was expected to embody the values, behaviors, and characteristics promoted by the Soviet state. The goal was to fully blend the republics into a unified Russian-speaking mass and work together to achieve a Communist utopia.

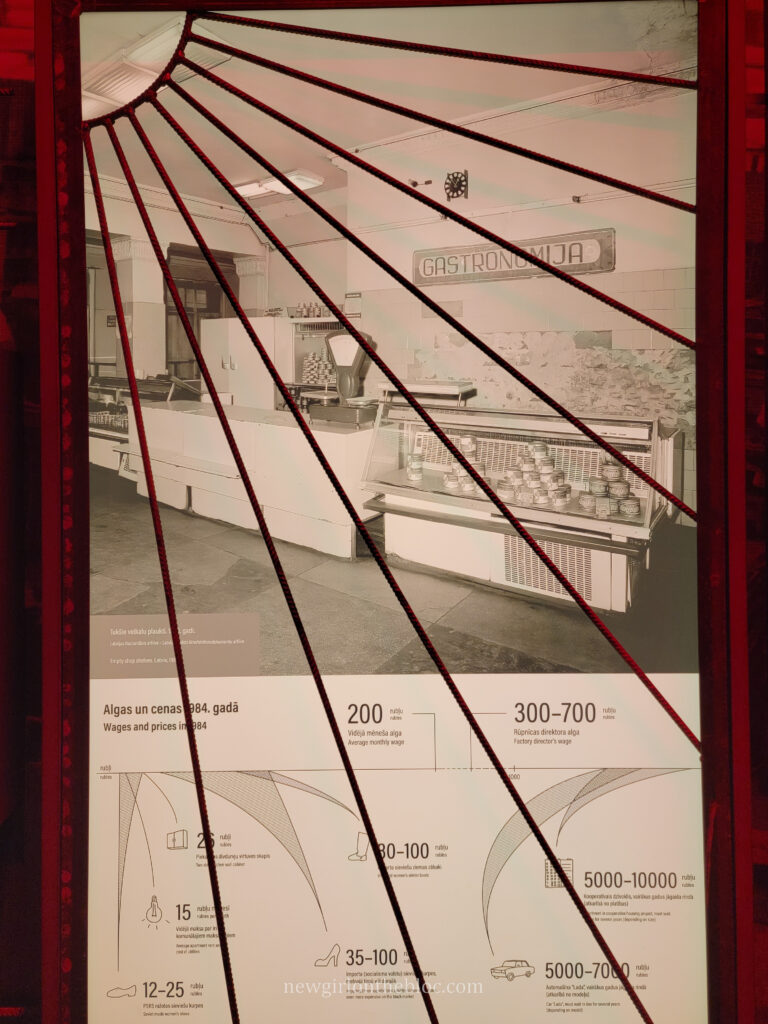

As agricultural production dropped due to the compulsory collective farming policy, many moved to the cities which Moscow was trying to heavily industrialize. “All-Union” enterprises were constructed, and workers were brought in from all over the Soviet Union to work in them. New residential districts popped up around the factories to house the influx of workers, and soon, the proportion of ethnic Latvians in the major cities fell below 50%. Moreover, the factories in Latvia exported what they produced, which led to a deficit of basic goods. With more people and less consumer goods available, people had to wait in long lines to get into shops and a black market emerged to fill in the gaps. But of course, such troubles only existed for the working class, as members of the nomenklatura had their own exclusive shops that offered goods not available to the public.

Learning Russian was compulsory in schools, and the curriculum had to adhere to the state’s atheistic and communist ideology. Communist youth organizations were created with the express intent of indoctrinating children beginning in kindergarten and lasting through university. The USSR attempted to purge Latvia’s collective memory by banning books that mentioned the country’s independence period and censoring foreign press. The KGB played a large role in ensuring that society only consumed media that glorified the Soviet Union.

Latvian Communist Party leaders briefly attempted to challenge Moscow and enact policies beneficial to Latvians such as promoting the Latvian language and culture, appointing ethnic Latvian to positions of power, and putting an end to forced migration. They condemned the forced Russification and assimilation of the local people. Unsurprisingly, these leaders swiftly lost their jobs, but a Latvian man named Arturs Pormals managed to smuggle the letter, now known as the 17 Latvian Communist Protest Letter, to the west where it sparked fiery condemnations after its publication in the press.

Latvia in the Cold War

The amount of Soviet forces stationed on Latvia’s territory increased as the Cold War reached new heights. Until the 1980s, Latvia’s strategically placed territory was home to many of the products of the arms race including nuclear weapons and intercontinental missiles. Latvian citizens were also compelled to serve in the military and were sent all over the Soviet Union and to conflict zones, such as Afghanistan, during the Cold War. Latvian soldiers were often discriminated against and beaten by other Soviet soldiers because of where they came from.

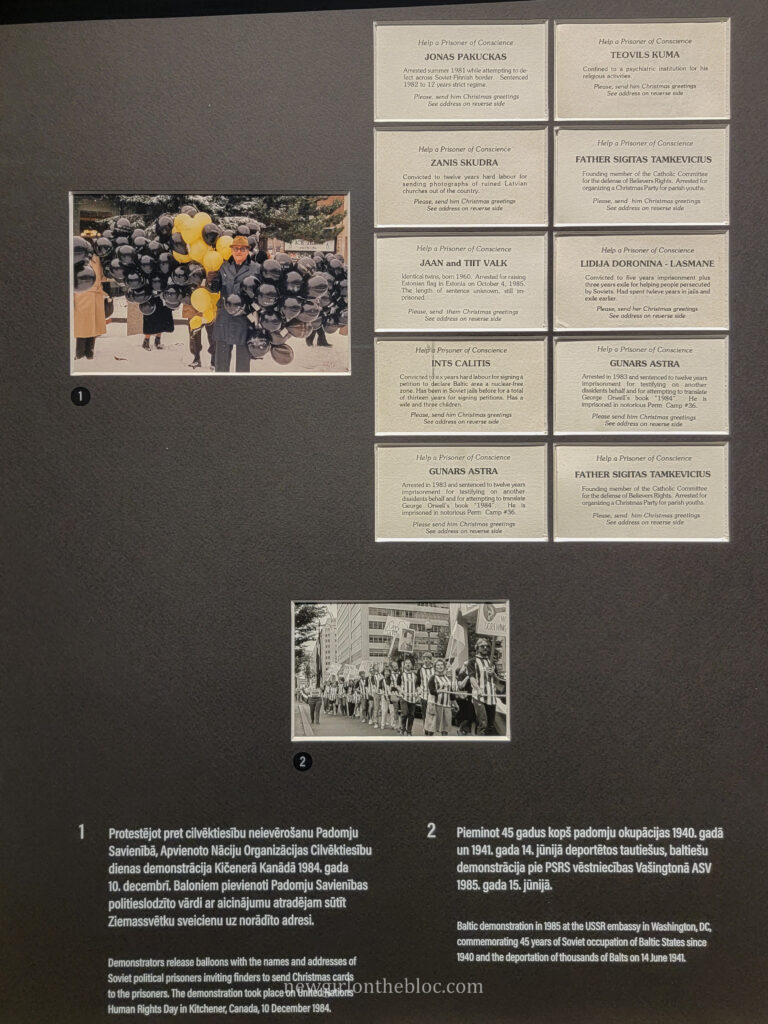

Despite the Soviet occupation of Latvia, Latvians who managed to flee or were in exile continued to fight for its liberation. Communities of Latvians created cultural and educational programs all over the world, and groups like the Committee for Free Latvia lobbied western governments to ensure they wouldn’t officially recognize the Soviet occupancy. Demonstrations were organized around the world denouncing the continued Soviet colonization of the Baltics. At one demonstration in Canada, demonstrators brought balloons filled with notes with the names and addresses of political prisoners encouraging those who found them to send them Christmas cards.

Starting in the 1950s, Latvian exiles were granted the ability to come to Latvian cities Riga, Jurmala, and Sigulda as tourists. Although they were under heavy surveillance by the KGB, exiles used these visits to their Latvian peers as a way to preserve their heritage. The ability to keep these contacts with Latvian residents proved especially useful during the late 1980s period known as the Baltic National Awakening.

The Third Latvian National Awakening & Latvian Independence

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev, the final leader of the former Soviet Union, implemented policies known as glasnost (“openness”) and perestroika (“restructuring”). These measures were aimed at revitalizing the struggling Soviet economy and promoting productivity, especially in the realms of consumer goods, the expansion of cooperative businesses, and the growth of the service sector. The introduction of glasnost removed restrictions on political freedoms within the Soviet Union. By loosening censorship laws to increase transparency, however, the USSR’s control over satellite states such as Latvia began to corrode.

Previously undisclosed issues that had been concealed by the Soviet central government in Moscow were publicly acknowledged, leading to a surge of dissatisfaction among the populations of the Baltic countries. The combination of factors such as the ongoing war in Afghanistan (1979-1989) and the Chernobyl nuclear disaster (1986) intensified grievances, which were expressed in a highly visible and politically significant manner. The liberalization efforts undertaken by the Soviet regime, which failed to consider the unique cultural sensitivities of the non-Russian nations, triggered large-scale protests against the Soviet government. Moscow had initially hoped that these nations would remain part of the USSR despite the easing of restrictions on freedom of speech and the display of national symbols such as pre-1940 flags. However, the situation deteriorated to such an extent that by the end of the 1980s, there were organized campaigns seeking complete independence from the Soviet Union.

The third Latvian National Awakening is widely considered to have commenced on 14 June 1987, coinciding with the anniversary of the 1941 deportations. On this significant day, the human rights organization known as “Helsinki-86,” established a year prior, mobilized individuals to lay flowers at the Freedom Monument. Erected in 1935, the Freedom Monument holds great symbolic importance as Latvia’s representation of independence. This was the first demonstration of its kind since the Soviet Union reoccupied Latvia in 1944.

The next year, two influential organizations emerged: the Popular Front of Latvia and the Latvian National Independence Movement (LNIM). These organizations were broad-based coalitions that united various social and political groups, including intellectuals, dissidents, nationalists, and members of the working class. Their primary goal was to advocate for the restoration of Latvia’s independence and the protection of the country’s cultural and national identity, which had been suppressed under Soviet rule.

On 7 October 1988, a massive public demonstration was held, demanding Latvia’s independence and the establishment of a fair judicial system. The following days, on 8 and 9 October, marked the inaugural congress of the Popular Front Of Latvia. With a membership of 200,000, this organization became the primary representative of the independence movement.

In 1989, the people of the Baltics organized a truly remarkable event. On August 23rd, 1.5 million people in the Baltics joined hands to form a continuous link singing all the way from Tallinn to Riga to Vilnius. Known as the Baltic Way, they formed a chain of people that was 660km long and demanded the government to publicly acknowledge the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact which brought the Baltic under Soviet influence and to grant the countries their independence.

In March 1990, new elections were held for the Supreme Soviet, leading to a victory for the supporters of independence. Subsequently, on 4 May 1990, the newly formed Supreme Soviet of the Latvian SSR passed a motion known as the “Declaration of Independence.” This motion called for the restoration of the inter-war Latvian state and the reinstatement of the 1922 Constitution.

However, in January 1991, pro-communist political factions attempted to regain Soviet control and restore their power. They resorted to the use of force in an effort to overthrow the newly established assembly. Nevertheless, Latvian demonstrators successfully prevented Soviet troops from reoccupying strategic positions, and these events became known as the “Days of the Barricades.”

On 19 August 1991, a failed coup d’état took place in Moscow, as a small group of prominent Soviet officials failed to regain power due to large-scale pro-democracy demonstrations in Russia. This significant event accelerated Latvia’s path towards independence. Following the coup’s failure, on 21 August 1991, the Supreme Soviet of the Latvian Republic announced that the transition period, which began with the declaration of independence on 4 May 1990, had concluded. Consequently, Latvia was proclaimed a fully independent nation, restoring the legal foundations of statehood that existed prior to the occupation on 17 June 1940.

Works Cited

“Brief History of Latvia – Honorary Consulate General of the Republic of Latvia in Jakarta.” Latvia.or.id, 2023, www.latvia.or.id/history_of_latvia_in_brief.

Fokrote, Liva. Christianity in Latvia in the Twentieth Century. 2000, digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1039&context=seminary_masters.

“History.” Thebalticway.eu, 2014, www.thebalticway.eu/en/history/.

“History of Latvia: A Brief Synopsis.” Mfa.gov.lv, 2014, www2.mfa.gov.lv/en/usa/culture/history-of-latvia-a-brief-synopsis#:~:text=Latvia%20was%20originally%20settled%20by,the%2012th%20and%2013th%20centuries.

Johnson, Emily. “‘My Soul Is in a Corset’: In Letters from Stalin’s Labour Camps, Glimpses of Soviet Oppression.” Scroll.in, Scroll.in, 16 May 2017, scroll.in/article/837005/my-soul-is-in-a-corset-in-letters-from-stalins-labour-camps-glimpses-of-soviet-oppression.

LLTA Lauku Celotajs. “Latvian Red Riflemen.” Militaryheritagetourism.info, 2021, militaryheritagetourism.info/en/military/topics/view/83.

Mārtiņš Ķibilds. “The Heroism, Banditry and Naivete of the Forest Brothers.” Eng.lsm.lv, LSM, 2019, eng.lsm.lv/article/culture/history/the-heroism-banditry-and-naivete-of-the-forest-brothers.a311024/.

Nelsson, Richard. “The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact – Archive, August 1939.” The Guardian, The Guardian, 24 July 2019, www.theguardian.com/world/from-the-archive-blog/2019/jul/24/molotov-ribbentrop-pact-germany-russia-1939.

Learn to speak russian

Travel with ease & dive into the culture, history & lifestyle of post-Soviet countries

free russian learning materials

Melissa

Get the Goods

Head over to the Language & Travel Shop to check out my favorite goodies I use for learning Russian and traveling! I've compiled all my favorite products I use when #onthebloc so that you can benefit from them when you travel abroad. Help yourself prepare and support this blog at the same time :) Счастливого пути!

carry-on goods

gifts for travelers

photography

apparel & accessories

textbooks & readers

luggage & bags

categories

#oTB essentials

Russian-Speaking Travel Destinations

use your new russian skills in real life!

Belarus

EASTERN EUROPE

central Asia

central Asia

Eurasia

Russia

Kyrgyzstan

armenia

Moldova

Kazakhstan

eastern europe

read »

read »

read »

read »

read »

read »

The caucasus