Soviet Nonconformist Art at the Zimmerli Art Museum

The Zimmerli Museum is an art museum near Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey which holds the largest collection of Soviet Nonconformist art in the U.S. The Zimmerli is free for the public, and includes two floors dedicated to Russian art. The collections span several art movements to give visitors historical context, but focuses on the period from 1956 to 1991, Khrushchev’s Thaw to Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost, that saw a relaxation of artistic censorship that dominated the early 20th century. This is when Soviet Nonconformist Art movement began to grow.

Truth be told, art didn’t use to interest me much. I would visit museums looking at the art on the walls with curiosity as to how people read into the strokes of paint as anything other than …paint. What I was missing was the context behind the art. What cultural, political, economic, or social movements were taking place when a piece was being created.

The Zimmerli does a fantastic job of transporting you to this time period so you can understand these factors that influenced the art and the sheer amount of courage it must have taken to compose them.

What was Socialist Realism?

At the turn of the 19th century, Russian art was at its peak of artistic expression and experimentation. The avant-garde movement had made its way to Russia, and avant-garde artists became enthralled with using abstract art to usher in equity and unity among all social classes. In 1932, however, Stalin introduced sweeping censorship laws known as Socialist Realism which established it as the only acceptable art style in the Soviet Union. As a result, all existing artistic groups were dissolved and reorganized under strict control of the Communist Party. Art that furnished the walls of art museums were removed and put into storage where they collected dust for several decades. Artists who did not conform to the guidelines of Socialist Realism were prohibited from displaying their art or even purchasing art supplies. In addition to being forced out of their positions, they were often sent to gulags, as was common for those considered to be undermining the success of Communism during Stalin’s Great Purges.

The parameters that defined Socialist Realism were dogmatic and principally aligned with Communist ideology. Art created during this era was required to be relevant and understandable to the worker, depictions of realistic, everyday life, and supportive of the aims of the State and the Party. The avant-garde art movement that had gained traction in the early 20th century was considered too abstract and unintelligible to the Soviet person, and thus banned under Socialist Realism restrictions.

Socialist Realism was used as propaganda to glorify and promote the “New Soviet Person” – the archetype of the ideal Soviet citizen. The “New Soviet Person” was to have all the traits and qualities that would advance the socialist revolution such as strength, literacy, good health, selflessness, and adherence to Marxism–Leninism. The art under Socialist Realism largely depicted scenes of the hard-working proletariat and the Communist utopia they sought to achieve.

The Thaw & The Rise of Soviet Nonconformist Art

After 31 years in power persecuting anyone who went against Communist ideals, Joseph Stalin died in 1953. Once Nikita Khrushchev took power and denounced much of Stalin’s authoritarian policies, dissident artists began circulating works of art that went against the restrictive policies of Socialist Realism.

Although many of the penalties that existed under Stalin were relaxed, these artists still risked being imprisoned, harassed by the government, and impoverished for going against the strict parameters of Socialist Realism.

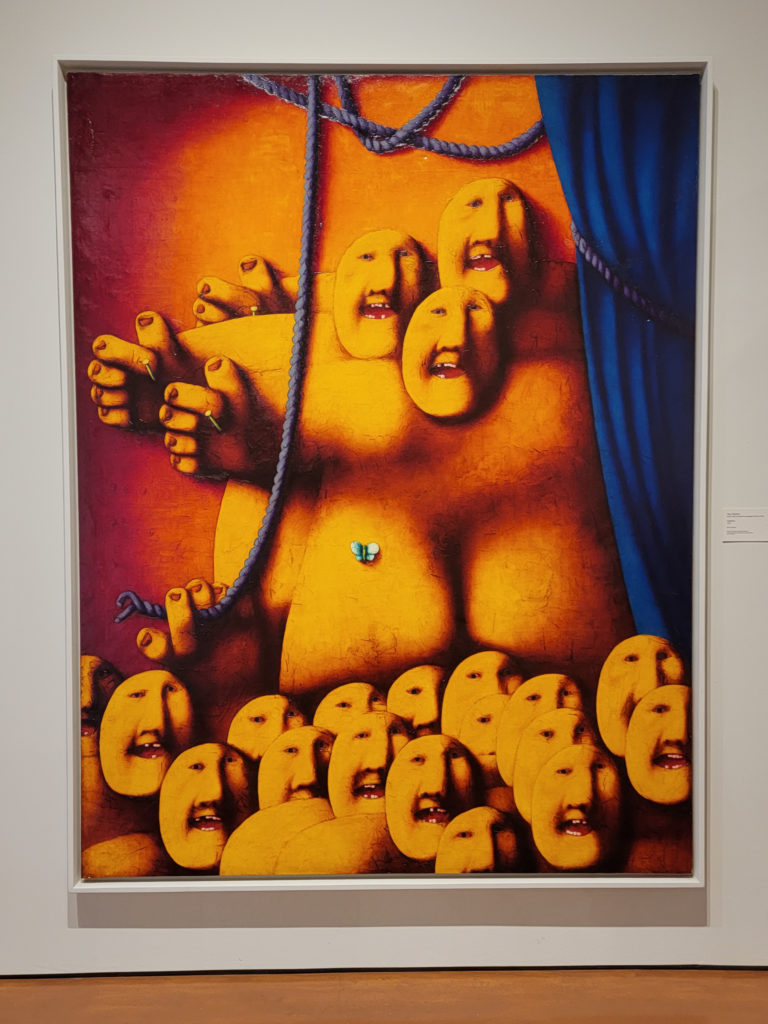

This art movement, Soviet Nonconformist Art, draws upon the art styles that had once bloomed at the turn of the century and gained international recognition only to be banned by Stalin’s repressive art policies. These artists drew inspiration from the avant-garde era and built upon the art styles with themes and political commentary on their experiences in the USSR.

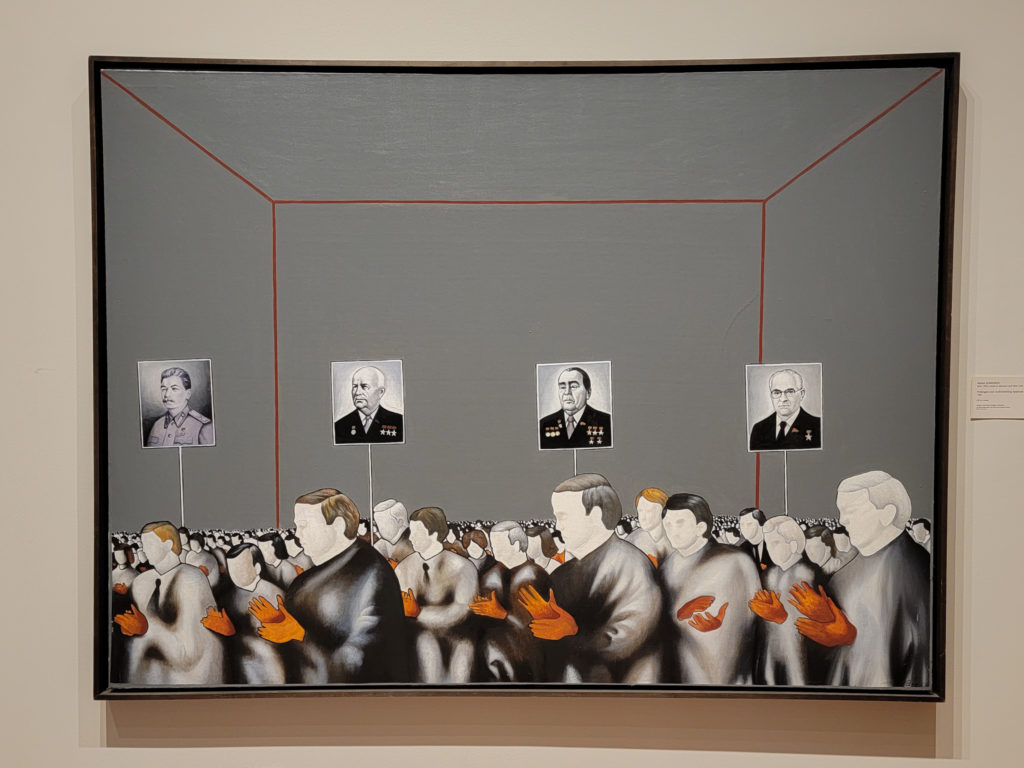

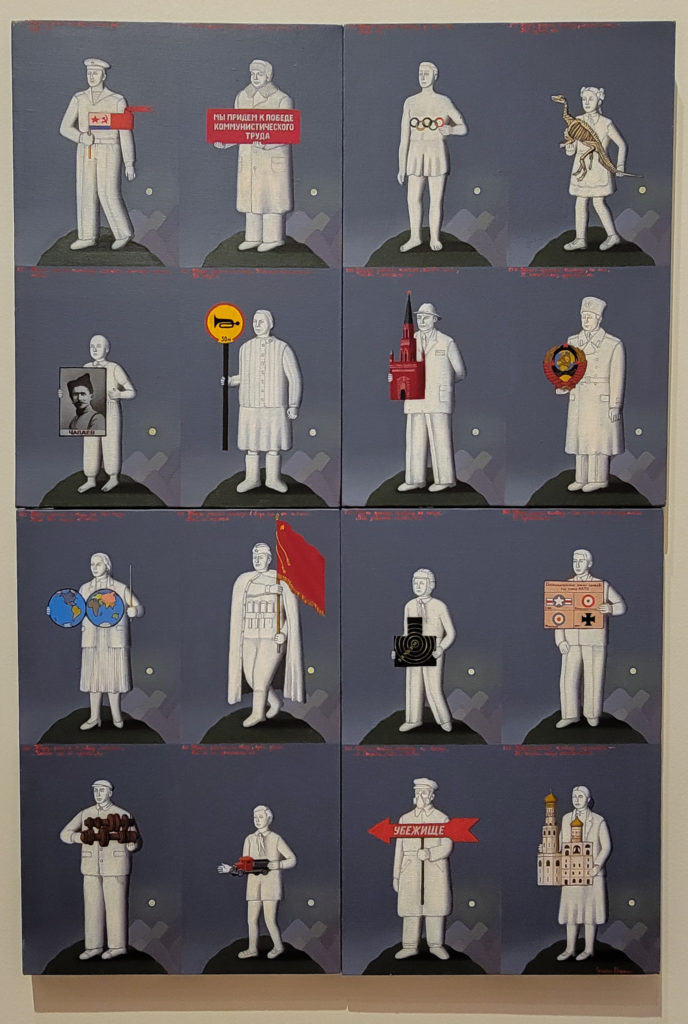

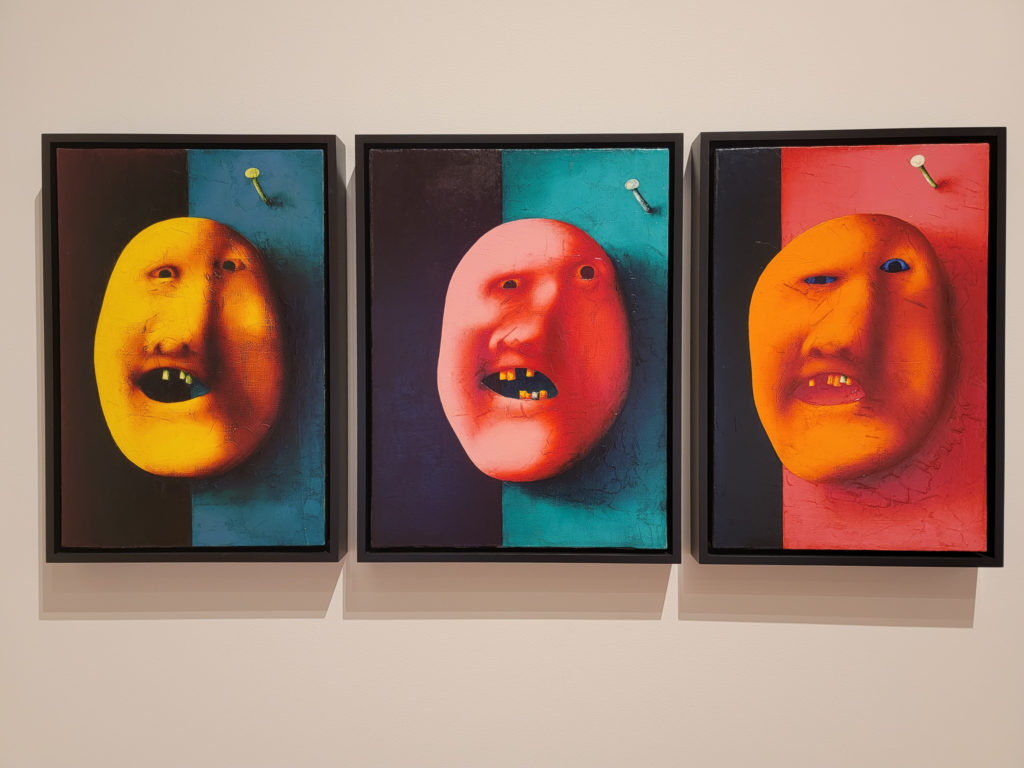

The most daring of the Nonconformist Art became known as “Sots Art” – short for the Russian word for socialist. Sots art became extremely influential during the 70s and 80s among nonconformist artists who sought to examine societal issues, mock Party ideology, highlight the grey, monotonous life that bore from Party policy, and above all, to mock a fundamental irony of Soviet life.

Sots artists employed visuals used repeatedly in Socialist Realism propaganda such as red banners, posters, slogans, and even Socialist Realism art itself to openly critique the regime. This Soviet Nonconformist Art, including Sots Art, is the focus of the Zimmerli Museum in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Learn the Historical Context of the Era

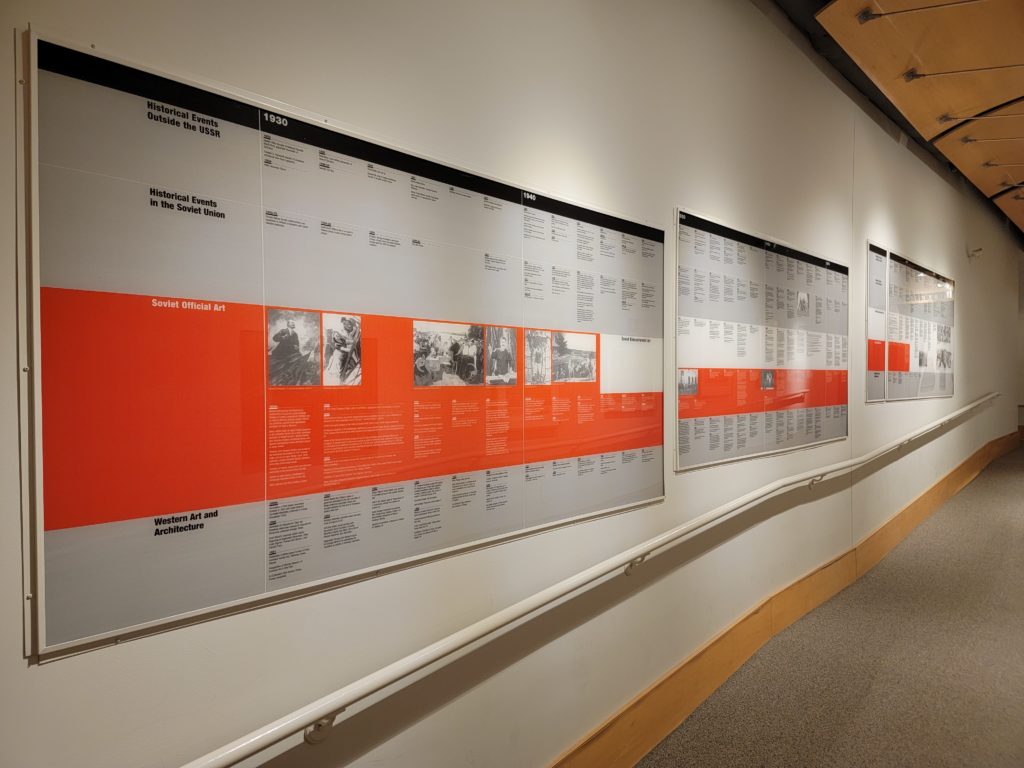

What I appreciated most about the Zimmerli’s Soviet Nonconformist Art exhibition was the amount of historical context that the museum provided alongside the art itself. The very beginning of the exhibit is a hallway lined with socialist realism pieces on one side, and on the other, four stacked timelines: historical events outside of the USSR, historical events in the USSR, Soviet official art, and Western art and architecture. This gives visitors the opportunity to really picture what was happening around the world in history before, during, and after the art was produced. In my opinion, this was crucial to understanding the true gravity of the nonconformist art in the exhibition.

If you’d like to see the collection of Soviet Nonconformist art for yourself, the Zimmerli Museum is open on Wednesdays-Sundays and provides free admission to guests. You can also see the collection pieces on their website.

Birth of a Hero | Grisha Bruskin | 1985

Learn to speak russian

Travel with ease & dive into the culture, history & lifestyle of post-Soviet countries

free russian learning materials

Melissa

Get the Goods

Head over to the Language & Travel Shop to check out my favorite goodies I use for learning Russian and traveling! I've compiled all my favorite products I use when #onthebloc so that you can benefit from them when you travel abroad. Help yourself prepare and support this blog at the same time :) Счастливого пути!

carry-on goods

gifts for travelers

photography

apparel & accessories

textbooks & readers

luggage & bags

categories

#oTB essentials

Russian-Speaking Travel Destinations

use your new russian skills in real life!

Belarus

EASTERN EUROPE

central Asia

central Asia

Eurasia

Russia

Kyrgyzstan

armenia

Moldova

Kazakhstan

eastern europe

read »

read »

read »

read »

read »

read »

The caucasus